Cute But Tough – The Arctic Fox

6 minute read – “Winter Is Here” series continues with a species well suited to cold conditions – Arctic Fox!

The Arctic Fox is super cute, we all agree, but don’t be fooled by its appearance, this is one tough cookie! Often referred to by scientists as Chionophiles, meaning ‘snow lover’, it is one of only a few species that have adapted1Watch our 360 video on Arctic Fox Adaptations to thrive in the harshest of winter conditions and survive some of the lowest temperatures on earth, living year round in the Circumpolar arctic. So, how does this cute, yet tough, canid survive such an environment?

Wearing its winter coat of white, the Arctic Fox can easily be mistaken for a small mound of snow. In fact, they are so well camouflaged, visitors to Yukon Wildlife Preserve often have a hard time recognising one when it is only a feet away from them. The thick white tail covers the dark eyes and nose allowing the animal to almost disappear against the snowy background. The tail further acts to wrap around the body or cover the face for added insulating protection, whilst thick fur on the paws provides protection from the snow and ice and increases grip on slippery surfaces. As well as the ability to camouflage itself for protection against predators, the white colour is thought to have better insulating properties, with greater air pockets than coloured hair to trap body heat.

The depth of the fur is 200% greater in winter with a dense undercoat of 8 lbs and an estimated 20,000 hairs per cm2. In comparison, humans have a range of approximately 124-200 hairs per cm2.

The Arctic Fox is not always fluffy and white, though. They shed their winter fur to a sleek summer coat, and are the only member of the Fox family who sheds to a different colour, making them quite unique. Instead of a thick white fur, they spend the arctic summer a colour-blend of browns and greys – allowing them to continue camouflaging to their environment year round.

Arctic Fox is the only fox that sheds its winter coat to a different colour, allowing them to blend in to their environment year round.

A compact predator with small ears, a short snout, neck and legs, the Arctic Fox is much smaller than the Red Fox. This physical adaptation provides a low surface area to volume ratio which means there is less surface area from which to lose heat. This is one of the reasons that Arctic Fox will curl into a ball when resting – by reducing the exposed surface area, energy loss is less and heat retention is maximized. Front and hind legs are tucked underneath the body, exposing to the frigid air only the thickest, and warmest fur. The head is placed on the front paws, and the tail wraps around the face. Arctic Foxes are able to slow their winter basal metabolic rate to around 25% less than in the summer. These adaptations allow them to withstand brutally cold temperatures either curled up on the snow or taking shelter in an existing den under the snow pack. This also helps them to survive longer without food; important when food is scarce in the dead of arctic winter.

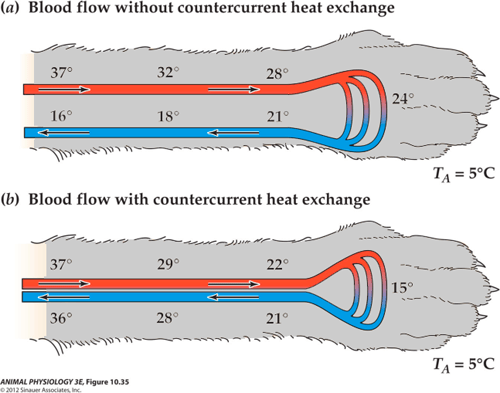

Keeping the blood flowing to the extremities is clearly important to an animal who spends its winter on the snow. The Arctic Fox has adapted its blood flow through its legs and paws for ultimate comfort and for thriving in such harsh winter conditions. This impressive heat conserving adaptation is called the countercurrent heat exchange.

To understand how this works, let’s first look at what happens without the adaptation – in species like humans. Warm blood from the heart courses down the leg straight to the feet. If those feet are standing on icy-cold ground the warm blood will cool quickly and lots of energy will be used to keep the feet as warm as the body. This cooled blood then returns straight to the heart to be warmed, requiring more energy and resulting in an overall lower body temperature.

Source bio.miami.edu/dana/360/360F18_9c.html

Instead, this physiological adaptation in a species such as the Arctic Fox means that the vein and artery in the leg run very close together allowing warm blood going to the foot to heat up the cold blood returning from the foot. In a nutshell, the warm blood heats the returning colder blood that’s heading back up to the heart, and in exchange, the colder blood cools the warmer blood going to the feet. This means the feet are constantly cold, but just warm enough to keep the tissues from freezing. As a result, the overall body temperature is warmer, thanks to this neat energy-efficient system.

Omnivorous diets, meaning that both meat and plants are consumed, help keep the Arctic Fox adaptable to changing conditions. They are carnivorous in that they will eat meat – hunting small rodents like lemmings, but also scavenging from the kill sites of larger predators like wolves and polar bears. Much like a domestic dog may eat carrots and apples, the arctic fox will tolerate and consume foods such as bird eggs2Watch the Arctic Foxes at Yukon Wildlife Preserve get an Eggy Easter treat, berries and even seaweed.

A behavioural adaptation to thriving when remaining in a harshly cold environment is to conserve energy by not moving a lot when it is really cold. Arctic foxes will hunt and cache food during warmer temperatures, remembering where those caches are, so that they have snacks available when they really need them – without having to expend energy when temperatures drop.

Between the highly specialized physiological and behavioural adaptations explored in this blog the Arctic Fox is well equipped. Far from being perceived as only cute and fluffy, this is actually a tough species living where few others do. The arctic tundra in winter presents a harsh, nearly inhospitable environment, but for the Arctic Fox, it’s home.

Watch this BBC Earth video detailing the trials of a young Arctic Fox learning to hunt lemmings here!

Ella Pollock Shepherd

Animal Care Technician

very nice!

R

devorppa