Nest Box Mysteries

10 minute read –

Those bird houses do the same thing as the ones you might have in your backyard – provide a safe home for birds to lay their eggs and raise their young. Bird biologists usually call bird houses “nest boxes” when they’re used for ecological monitoring. Many kinds of birds, small mammals, and insects will use nest boxes in the same way that they use natural holes in trees. This makes nest boxes a good tool for biologists to use in order to get a glimpse of what might be happening in nature at a broader scale over time. But why is it important to monitor the birds that use nest boxes?

Holes in trees – cavities – are used by over 100 species of birds and small mammals. The cavity nesting ecological community consists of many complicated relationships that depend on one another. For example, birds such as woodpeckers are considered keystone species because without them excavating holes many other species like Tree Swallows and Mountain Bluebirds, which cannot excavate their own holes, wouldn’t have a home. If these types of important relationships are disrupted it may be a red flag indicating something is wrong at an ecosystem level. We know that climate change is having a bigger effect in the north when compared with more southern regions and as habitat changes as a result, so too will the biodiversity in the north. By simply monitoring the birds that use nest boxes, we might be able to get a sense of how the changes at play are affecting the north.

Fun facts about Mountain Bluebirds:

- Scientific name: Sialia currucoides

- Typical habitat: open woodlands

- Feeding habits: ground insect foraging

- Territoriality: defend nest cavity site and foraging area

- For more info: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Mountain_Bluebird/id

Fun facts about Tree Swallows:

- Scientific name: Tachycineta bicolor

- Typical habitat: open fields next to wooded areas and wetlands

- Feeding habits: aerial insect foraging

- Territoriality: defend nest cavity site

- For more info: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/tree_swallow

Monitoring nest boxes is a great way to learn about many important parts of birds’ lives. Some things that bird biologists monitor include: the species that used the box, the number of eggs laid, the number of those eggs that hatched, and the number of those young that grew up to leave the nest box on their own. Keeping track of the timing of all of these events is also very important because it can tell us if things are changing from year to year, or more importantly, over the long-term.

Dave Mossop, bird biologist at the Yukon Research Center at Yukon University (formerly Yukon College) and his summer students have been monitoring his system of nearly 50 nest boxes at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve every summer since 2006. I was one of his lucky student assistants in 2017. The nest boxes are placed on wildlife enclosure fence posts and the only tools you need to monitor them are a ladder, screwdriver, and a notebook with a pencil…and a good sense of balance. Checking the boxes involved driving around the roads within the Yukon Wildlife Preserve and stopping at each box. After balancing a short ladder on a fence post I carefully climbed up and unscrewed the box’s lid.

Over 85% percent of the boxes that were available for nesting over the course of the study were used by either birds or squirrels

Early in the summer there would sometimes be a nest with or without eggs, but no birds present. Luckily, each species had fairly distinct looking nests and eggs. Mountain Bluebirds typically had grass nests and light blue eggs; Tree Swallows tended to have a lot of feathers (many from waterfowl) in their nests and had off-white eggs; Chickadee nests consisted of mostly moss and had small light-coloured eggs with dark speckles; and squirrels had everything from grass to feathers, to moss, to housing insulation and candy wrappers in their nests. After taking note of what was in each box, I would screw the lid back on, tell Dave what I saw (he recorded everything on data sheets), and we would carry on to the next box. The same routine applied later in the summer when young birds were hatched. Sometimes protective adults would not leave the nest box even when the lid was unscrewed, so I would take note of what I could see, but more importantly, I would quickly screw the lid back on to reduce the stress to the birds. Once in a while, the adult birds (of either species) would raise a second brood in the same box. Every winter, all of the boxes were cleaned and repaired if necessary so any old nests wouldn’t discourage birds from using the boxes each spring.

By having a system of nest boxes in the same location that are checked every year – as opposed to putting up new boxes here and there for fun – data can be analyzed in a systematic way. Biologists can then examine the results and compare what they find with other similar studies. In 2018 I compiled and analyzed all of the data since 2006 and found some interesting results. The main species of interest that used the nest boxes were Tree Swallows and Mountain Bluebirds. Chickadees and Red Squirrels also used the boxes, but not as often.

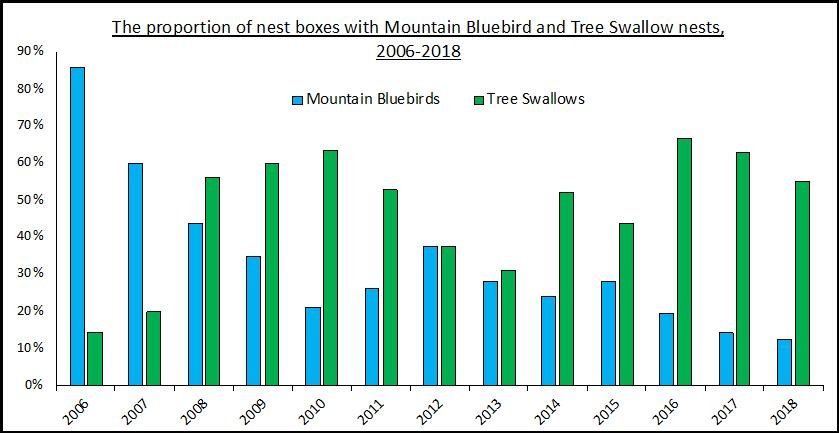

Overall, nest boxes were used very often. Over 85% percent of the boxes that were available for nesting over the course of the study were used by either birds or squirrels, the remaining 15% of boxes were unoccupied. One of the key results of the long-term data was that the proportion of Tree Swallow nests appeared to be fairly stable since the beginning of the study in 2006. Interestingly, Tree Swallows – like most other aerial insectivorous birds – have been found to be in decline in many other regions of North America, but that doesn’t appear to be true in southern Yukon. On the other hand, the proportion of Mountain Bluebird (which typically forage for insects on the ground rather than in the air) nests appeared to be slowly declining. Unfortunately, the reason for this decline is unknown. You can see the long-term trends for both species in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The proportion of boxes with Tree Swallow nests varied across years, but remained relatively stable, whereas the proportion of boxes with Mountain Bluebird nests declined in general.

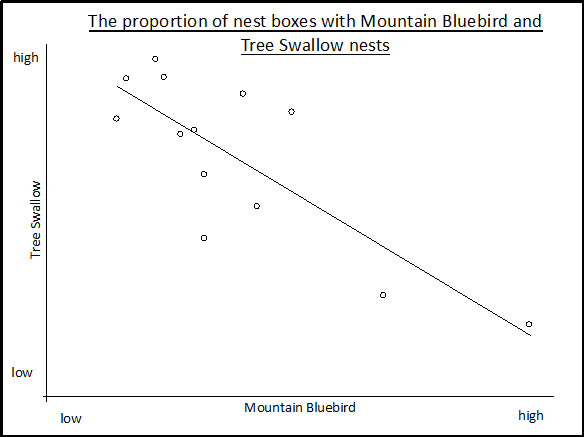

Mountain Bluebirds and Tree Swallows have overlapping ecological niches when it comes to nesting requirements. In other words, both species use the same types of cavity nests in generally the same place during generally the same time. This can create some tension – or competition for nest boxes. Based on the results of the study, it appeared that Mountain Bluebirds may have been the winners in this competition. Using statistics, I found the proportion of boxes with Mountain Bluebird nests could predict over 60% of the variation in the proportion of boxes with Tree Swallow nests (see Figure 2 below). So, when the proportion of Mountain Bluebird nests was greatest, the proportion of Tree Swallow nests was predictably lower; when the proportion of Mountain Bluebird nests was lowest, the proportion of Tree Swallow nests was predictably higher. This may help to partially explain why Tree Swallows appear to be doing relatively well in southern Yukon. Since Bluebirds have been less common recently, there has been less competition for nest boxes, potentially benefitting Tree Swallows. One of many big questions at large is what is causing the decline in Yukon’s Bluebirds?

Figure 2. This linear regression showed the proportion of boxes with Mountain Bluebird nests could significantly predict over 60% of the variation in the proportion of boxes with Tree Swallow nests. When the proportion of Mountain Bluebird nests was highest, the proportion of Tree Swallow nests was lower. When the proportion of Mountain Bluebird nests was lowest, the proportion of Tree Swallow nests was higher.

Just like anything in nature, science can help explain little pieces of it, but the big picture is almost always more complicated than humans can understand. The bad news is human-caused climate change is real and land use changes in combination with climate change may outpace the ability of ecological communities to keep up. The good news is that we can use good scientific techniques, such as nest box monitoring, to help answer questions and track change over time. We can then use the answers we get to help guide our decisions with the aim of maintaining a biologically diverse world. Decisions in land use planning, forest management, and mining (important Yukon activities) can benefit from such answers. So, next time you look at one of those bird houses you can ponder how some wooden boxes can help tell a few of nature’s stories and how those stories might lead to some very important questions.

This article was originally published in June 2020 with data from 2006-2018. In 2021 Executive Director, Jake Paleczny spoke with CBC Yukon and provided an update on some of what researchers are learning from these bird boxes. Listen here.

Sonny Parker

Guest Researcher / Author

Sonny Parker is a born and raised Yukoner. He grew up in Dawson and has always had a love for nature and adventure. This passion helped carry him through a B.Sc. in Environmental and Conservation Sciences. He’s had the privilege of obtaining a variety of interesting jobs (from wildland firefighting to hydrology to wildlife biology) in the Yukon that have engaged his love of the outdoors and science. He also has a passion for wildlife photography. Sonny looks forward to continuing to work, play, and learn in the north and encourages others to become stewards of our wild spaces. All photos and graphs by Sonny Parker.

Great article Sonny!

Great article Sonny. It will be really interesting to watch these trends as the years tick by. Kudos to Dave Mossop and all his wonderful summer students who have been collecting this important long-term data.

Thank you for this article, Sonny and for your work on the monitoring program and analysis.. It would be nice to see more bluebirds around – such a pretty bird. I have noticed their numbers declining over the 40 years I have lived in Whitehorse. Very grateful for the nest boxes provided, maintained and monitored by Dave Mossop, Yukon College (University) students and the Yukon Wildlife Preserve.

Hi Sonny,

I study Tree Swallows in central Pennsylvania. This was a fun read.

Thanks for sharing. It gave me some ideas to ponder as my research program evolves.

What happened to swallows at canyon creek. Haven’t showed up yet was counting on them to eat my mosquitos. Last year had lots got mosquito ponds below my house.

We had lots of swallows here at the Preserve this year, but then again there were A LOT of mosquitos too. We don’t think all the swallows could even keep up!