A Tale of Chasing the Sun and Losing the Clock

6 min read – this is a crosspost from Avery’s website Snail Tales.

I think about how my first few months living in the Yukon feel like the drawn-out, long sunrises and sunsets up here. They are often multicoloured, with bright hues and dark contrasts, and they seem to last ages. This is, apparently, all because of the Earth’s tilt and rotation. I was asking everyone about this my first few weeks here. I needed to understand why the sun seems to take longer to rise, fall and hover at the horizon compared to anywhere I’ve ever been. Turns out when you’re farther north, the sun takes a much shallower angle as it rises and sets! Instead of popping straight up and down like it does near the equator, it moves more horizontally across the sky.

Mountain goat cliff illumiated pink in the long winter sunrise. Photo credit: Jake Paleczny.

This makes the transition between night and day stretch out longer. Someone said to me, “Think of it like a ball rolling up and over a hill—if it goes straight up and down, it’s quick, but if it follows a more gradual slope, it takes longer. That’s basically what the sun is doing near the poles.” I’m thinking of making an animation of this to try to make more sense of it physically. This effect gets even more extreme as you go farther north. It’s why there is midnight sun near the summer solstice, and in winter, it gives us the long, drawn-out sunrises and sunsets that I have cherished and gawked at almost every day since I moved up. The territory is a mix of extremes: light and darkness, with a lot of expansive grey and blue sky in between. It’s 10am as I write this and the clouds are pink with sunrise.

Drawing by Avery Elias. The cabin I rent in the Boreal Forest.

Sometimes I feel like time is flying and I can’t seem to muster the energy to chase it. But just as the sun moves differently up here, my sense of time has changed too. The other day I was working a shift at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve and I asked my coworkers what they think about our relationship to time versus other animal’s relationship with it.

We got into a discussion about how time in the sense of minutes and hours is an abstract human-constructed concept. We are the only animals that track time like this. Every other animal seems to be deeply connected to their internal clocks and their circadian rhythms.

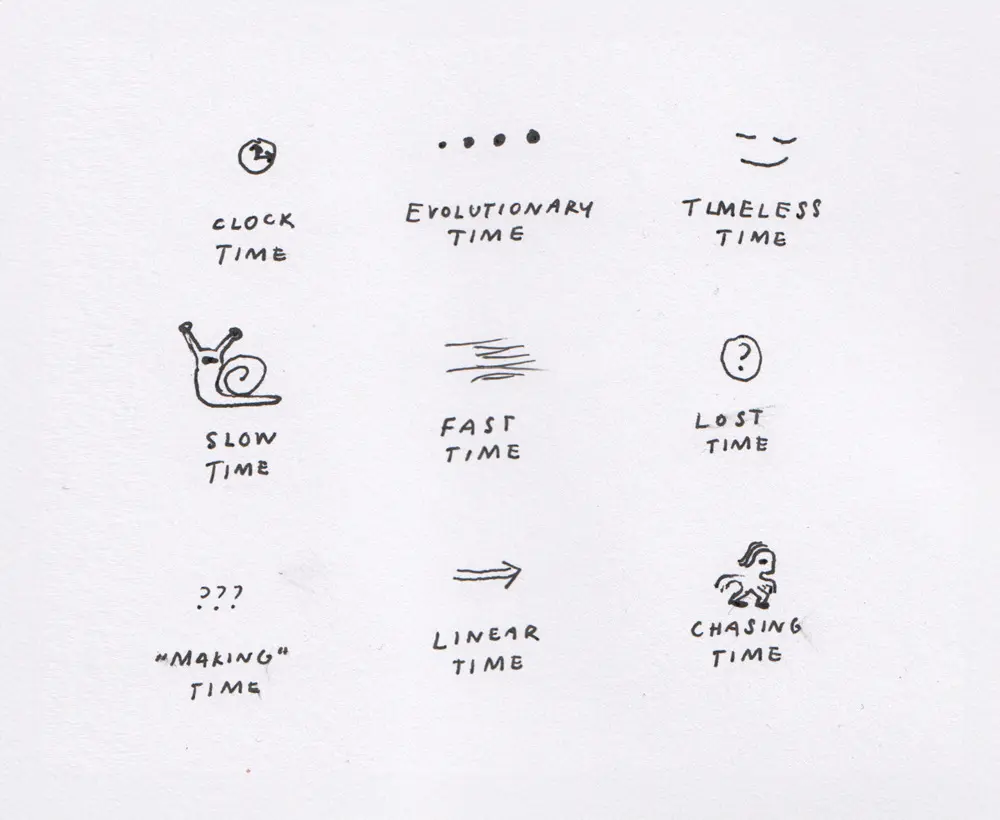

Humans are obsessed with time and trying to name it; we think we can control it, track it, chase it, kill it, steal it, make it and run out of it. The more time I spend with the wildlife in the Yukon, the more absurd and ridiculous these ideas become.

Illustration by Avery showing our connection with time.

The sun lingering on the horizon up here sometimes gives me the illusion of time stretching. I’ve started to feel that slowness elsewhere, like when I’m alone observing the musk ox. Here’s what I wrote in my journal one morning:

Being around the musk ox, I leave my personal human sense of clock time. I feel something different. I wonder if it is “evolutionary time”. The musk ox are an ancient species — they are considered ice age survivors. I learned today that they are one of the oldest surviving large herbivores on Earth. I am pulled into the physical and spiritual around them. Maybe that’s a different place to be from the linear, the daily clock we all measure our “own” minutes, hours, days, weeks, years by. The musk ox is not keeping track of time in this way. They use their internal clocks. All the animals here do.

After the discussion with my coworkers, I ponder this difference between the way we think of time and the relationship the musk ox have with it. Is it a contributor to the illusion of separation we’ve created between us and the wildlife? Between human beings and the natural world? It only took a few shifts working at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve to realize I was sensing something powerful and healing about the places I’ve been spending time in— the preserve, the North, and my cabin in the Boreal forest*.

I couldn’t stop thinking about the illusion I had been living under— the idea that we are separate from the animals and the wild. Far away in our cities, being raised to believe that humans are the centre of everything. We’ve elevated ourselves but we are simply part of nature like the rest of these animals. It feels silly to have to even state this and maybe many of you already understand it. But I grew up in a big city and it’s taken me living in a forest, in a territory with one of the lowest population densities in the world to really make some sense of it.

*The boreal forest, also known as the snow forest, is a biome characterized by snowy winters and freezing temperatures. It’s the world’s largest land biome. This forest converts carbon dioxide into oxygen on a massive scale (the air is very good up here ☺ ). The snow stays on the ground for many, many months.

Learning from the wild

I heard a term recently: Ecological Identity. It bears the questions: Who are we in relation to nature? How do we fit with what’s around us? I wrote that the musk ox are considered ice age survivors. When I give my tours to visitors at the preserve, people are often shocked and intrigued by this information. I like to remind them that we as homo sapiens are also ice age survivors! Multiple ice ages* in fact: at least two in the last 200,000 years.

Yet our evolutionary paths have remarkably diverged. The lives of the musk ox are still closely attuned to the rhythms of nature, as they were during the ice age. When I’m around them, it feels evident that they are living in harmony with their surroundings. I sense that they are in a deep state of attention. In a way, are they living in the timeless? We’ve created cities and systems that can obscure the natural rhythms of day and night, the seasons, and the ecosystems around us. These differences highlight not just how far we’ve come, but also how much we might still learn from the creatures who remain deeply connected to this earth we share. The only time I’ve been able to feel this kind of harmony for an extended period is when I’m on long camping trips or boat rides where I feel almost lost in the sea. It makes me think that my over-structured, calendar relationship with time is like a surface-level experience of life. Like the restless, choppy waves at the surface of the ocean.

The musk ox relationship with time might be more like the water deep below the surface, where things appear calm and more still. In a way, I feel consoled by the lesson of the musk ox on this day. If the Yukon’s light has changed how I see time, the musk ox has helped how I feel it.

*When people say “the last ice age”, they’re usually referring to the last glacial period (that ended around 10,000 years ago), when ice sheets covered much more of the planet. I recently learned from my coworker at the preserve, Danial, that scientifically speaking, we’re technically still living in an ice age since there is permanent ice at the poles. What we’re in now is an interglacial period, meaning a warmer phase within an ongoing ice age. If things followed the natural cycle, we’d eventually head back into a glacial period, but human-driven climate change is disrupting that pattern.

Anywho, that’s all the *time* I have for today. Maybe time isn’t something to track, chase, or control. Maybe, like the musk ox and the Yukon sun, it’s something to settle into.

Remember: there’s no time like the present!

I would love to hear any thoughts that are sparked from reading or tales of your own. There’s a comment section below.

Thanks for taking the scenic route with me,

Avery Elias

She/Her - Wildlife Interpreter

Avery’s journey to the Yukon Wildlife Preserve began during a vacation in August 2024, when she was living in Vancouver and looking for a quieter, wilder life. Having spent the past two summers on farms in Oregon and the Vancouver area, Avery was drawn to the wild beauty and close-knit community of the Yukon. Now, she’s excited to join the team as a wildlife interpreter. Outside the preserve, Avery works as an illustrator, animator, painter, and digital designer, collaborating with local businesses and pursuing her own creative projects.

This is beautiful, Avery. Thank you for sharing your wisdom and your lovely drawings.

Thank you so much Jo. I’m delighted it resonated with you.

The world is too much with us,

Late and soon;

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers, Little we see in nature that is ours. We have given our hearts away–a sordid boon!

William Wordsworth

Beautiful! Thank you for sharing, Betty