Peashrub Pull

3 min read –

What’s happening to the bushes beside the bison habitat?

These bushes are Siberian peashrub (Caragana arborescens). They are also known as the pea-tree or caragana. This species doesn’t belong here; it is an invasive species.

Yukon Wildlife Preserve represents the territory’s natural ecosystem. To keep the Preserve natural, we are removing the Siberian peashrubs. Willows, roses, and wildflowers will soon be growing here instead. A new trail will allow for better animal and plant viewing.

• • •

The yellow flowers of Siberian peashrubs made them an attractive garden plant.

Peashrub image copyright A. Barra, CC BY 3.0.

How did they get here?

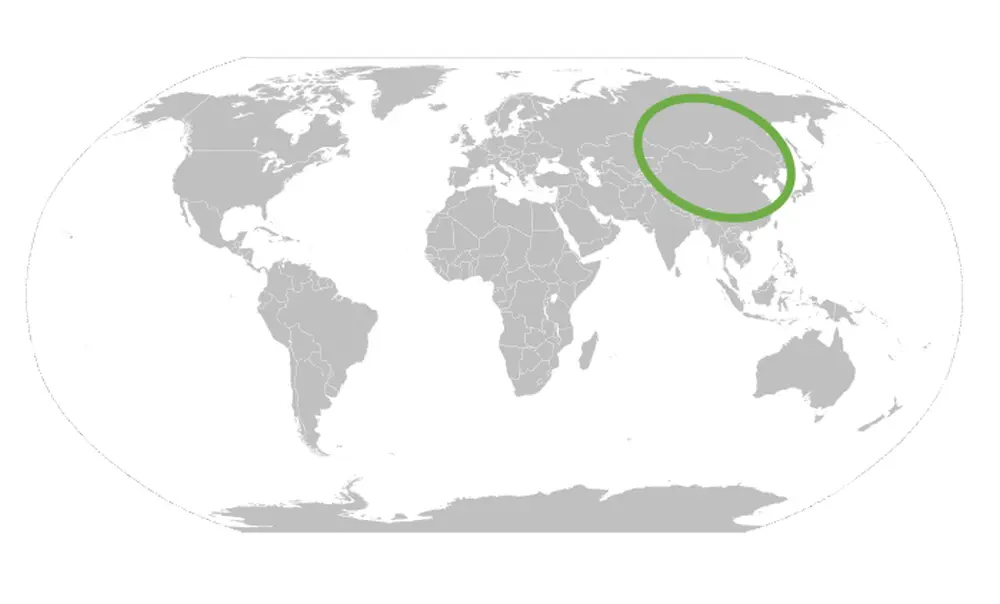

Siberian peashrubs are from Siberia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and northern and eastern China. They were first introduced to North America over 130 years ago. Since then, they have spread across many parts of Canada and the United States.

People plant Siberian peashrubs in gardens for their yellow flowers. They are also planted as windbreaks and to hold soil in place. In many places they are now out of control.

• • •

What makes a species invasive?

An invasive species:

- Does not naturally live in this ecosystem

- Has negative impact on the ecosystem, humans, or both

- Spreads rapidly and aggressively, causing major damage to the environment.

• • •

Foxtail barley (Hordeum jubatum) is also an invasive species. At the Preserve, we are working to remove this as well.

What can you do?

Invasive plants threaten Yukon’s natural balance. Even some common garden plants can become invasive! By being careful what we plant in our homes and neighbourhoods, we can all contribute to a more natural territory.

• • •

Haskap berry bushes are one of many native plants that can replace invasive Siberian peashrubs in your garden. Haskap image copyright Opiola J., CC BY-SA 3.0.

Want more information?

Want more information on safer gardening? The Yukon Invasive Species Council has many resources: www.YukonInvasives.com.

• • •

We thank the Yukon Foundation for funding to support invasive species removal and ecological restoration.

We thank Lotteries Yukon for funding to support trail construction.

We also thank our summer Nature Camp participants for their hard work in removing Siberian peashrubs.

• • •

Education Team

This project is brought to you by the hard work and creativity of the Education team at Yukon Wildlife Preserve.

6 Comments

Submit a Comment

Box 20191

Whitehorse, Yukon

Y1A 7A2

I’m curious as to why there is so much concern about invasive species? Isn’t it true that ecosystems are constantly evolving as weather and other factors change? Surely many of the plant and animal species extant in the Yukon 10,000 years ago, or 24,000 years ago, or 120,000 were significantly different from each other, and also from today! If during previous warming or cooling cycles, people had tried to maintain the status quo, the territory would be less, not more diverse, than it is today?

Further to my last post, I’m pretty sure that using phylogenetics correlated to geography, it would be relatively certain to prove that essentially all species extant anywhere in the world were, at one time or another, invasive. Camels and horses invaded the old world from the new world, all the deer species, including elk, caribou and moose invaded the new world from the old, and even the Haskap berry, which is now a circumpolar boreal regular, originated like the peashrub, in Siberia. If climate change is occurring perhaps we should allow nature to adjust.

Excellent points and refreshing insight!

And the irony of the whole invasive species obsession is that the most invasive species of all are…..the human species!!

Thanks for your comments and questions! Invasive species are a modern concern in part because they are spreading orders of magnitude faster than in previous timeframes. Additionally, ecosystems that are already under pressure from other human impacts are also less resilient and able to adapt to change. Many invasive species, including Siberian peashrub, grow quite well in disturbed areas which prevents other species from re-growing; this leads to a single-species forest of shrubs with little other life present.

Part of what defines an invasive species is that it has a net negative impact on other essential elements of the ecosystem. Yukon Invasive Species Council defines invasive species as “a species… that is not native (to Yukon/an ecosystem) and whose introduction or spread is likely to have net negative effects on our society, our economy, our environment, or our health.”

Even a highly invasive species is not all bad. A student researcher at Yukon University found interesting uses for white sweetclover, one of the territory’s most invasive species, in mine remediation and pollution control. While the research is ongoing, you can read a summary of it in this CBC piece: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/yukon-university-white-sweet-clover-mine-remediaton-research-1.6914096.

Like so many things in nature, balance is the key. At Yukon Wildlife Preserve, we are removing invasive species to help better reflect the natural ecosystems we showcase and to improve the resiliency of our ecosystems for years to come. Replacing the Siberian peashrubs with willows and other native species is just one part of the plan; we look forward to sharing more of it with you in the future!

Thank you for your reply. That said, I would question at least two of the assertions you’ve made therein. The first is that this particular invasion is “progressing orders of magnitude faster than previous time frames.” It’s a bold statement considering the limited information available. What is your timeframe reference? Are you talking about observations made in the past fifty, one-hundred, one-thousand, or hundred thousand years, for example? The second is that peashrubs will have a net negative effect on the ecosystem. I think long-term studies and supporting citations would be needed to substantiate both statements.

The decline of native species can often take a very long time, and those declines are seldom complete or permanent in a land area as large as the Yukon with many examples of refugia from similar ecosystem changes in the past. Furthermore, the rise and expansion of non-native species are also subject to a variety of naturally occurring limiting factors. The colonisation of new species with the decline of old species can be represented graphically as temporal curves that clearly demonstrate increased biodiversity through most of the time representing a transition of dominant species. Finally, peashrub in particular, do offer some benefits to the existing ecosystem. For example, it is known to be an excellent choice for soil stabilisation, something we will likely need more of as temperatures increase in the north with the potential for erosion also increasing. The peashrub has the ability to convert nitrogen to ammonia-nitrogen fixation at a much lower temperature than many other species, and it’s used as a food source by a number of native bird and animal species.

I guess what I’m saying is that you can make arguments for and against “invasive species” quite easily, and despite the fact that humans can play a part in the introduction and spread of new players, just because something wasn’t here in the recent past, doesn’t mean that it can’t contribute something positive in the present or in the future. People often seek to control the natural world in ways that we assume will benefit nature without truly understanding the big picture.

Thanks for engaging. I think part of the answer has to do with the difference between exotic and invasive species. Yukon’s Conservation Data Centre has a comprehensive list of exotic species. The 223 species on their list are species that are or were present in Yukon but are not considered part of the natural ecosystem (entering the territory in the last 150 years or so); out of those, less than 10% are considered highly invasive.

For more information on invasive species in general, I’d refer you to the subject matter experts: the Yukon Invasive Species Council and Yukon Conservation Data Centre. I also did a little digging into the Conservation Data Centre’s assessment of peashrubs as medium-to-high risk of invasiveness. One of the major reports assessing the impact of this species was completed in 2012 by Shortt and Vamosi (https://t.ly/D3yE4). In brief, the authors conclude that the information available about Siberian peashrubs suggests “several aspects of its biology show its considerable potential to negatively impact ecosystems”. Shortt and Vamosi note that the one available field study of peashrub invasiveness found that increases in peashrub density were associated with significant declines in native shrub diversity in Elk Island National Park.

I would agree, and I suspect you would be hard-pressed to find a scientist who disagrees, that additional research is needed to better understand the nature and impacts of invasive species. Unfortunately, there is insufficient funding, expertise, and time to study each of Yukon’s 223 exotic species in detail; this leaves us relying on generalizations based on biological characteristics of each species.

To summarize, I’d like to suggest a slight edit to your conclusion. I agree that is easy to make arguments for and against exotic species. Just because something wasn’t here in the recent past does not mean it cannot have a positive contribution. When we are talking about invasive species in particular, however, they are defined by a net negative impact on the world around them and we should think carefully about how to minimize that negative impact on the surrounding environment.

We made the decision to remove the peashrubs at the Preserve because 1) our mandate is to represent Yukon’s natural ecosystems, whereas the peashrubs were planted by humans, 2) we want to minimize the risk of spreading a species deemed invasive by the subject matter experts, and 3) we want to provide opportunities for further biodiversity on-site.

– Neil

Manager Education & Programming