Bat Talk: How do you listen to what you can’t hear?

This article was made possible thanks to support from the Environmental Awareness Fund. Engage and educate yourself in this 10-part blog series, about Yukon Biodiversity.

10 minute Read.

Banner image photo credit: Justine Benjamin

If you’re an enthusiast for the sounds that airborne animals make, you can absolutely drown yourself in bird call resources from written guide books to audio recordings on birdwatching apps. But what about bats? These little bug-eating wonders are also screaming around the sky but they are much harder to hear. In fact, they are almost impossible to hear! While some bat calls are audible, a lot of them fall outside of the range of human hearing. So how can we get in on the bat gossip?

Let’s tackle the basics first: how do bats make sound? Bats use echolocation, also referred to as “bio sonar” which essentially lets them “see” using sound. This a very useful technique for creatures that are almost exclusively active in the dark. It’s definitely more effective than my method of locating objects in the dark which is usually by painfully smacking into them with my knees and pinky toes. Echolocating animals emit a calls out into their environment and listen to the echoes of those calls to determine the location of objects or prey in their vicinity. Most bats emit these calls by contracting their voice box (larynx) although a few species click their tongues. The frequency of these calls is mostly in the ultrasonic range i.e. they fall outside the human ear’s audibility limit (around 20,00 hertz or higher). The sound travels out of their mouth (or sometimes nostrils!) and the returning echoes are picked up by their highly specialized ears. The outer shape, size, and wrinkles of a bats ear are thought to help capture and funnel the echoes to their inner ear which has receptors that are tuned to the specific frequencies of the bats call and the corresponding echo. Neat right? I think it’s pretty neat.

A tail get set up for mark recapture of little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) in the field. Photo credit: Justine Benjamin

Bats have different calls for different occasions; their “I’m about to eat this bug!” call is different from their general “Where are all the things around me?” call. A smarter way to say this is bat vocalizations include social calls, navigation calls, approach calls, and feeding buzzes. Navigation calls (also known as travel or search calls) are exactly what it says on the label, they’re the call bats use to determine the relative location of objects around them as the bop around in the night sky. Similar to a navigation call is an approach call which bats use when they’re closing in on a bug, heading towards a landing spot, or if they’re flying around in a cluttered environment like somewhere with lots of vegetation. Think of it as a bat proximity warning.

Social calls are often lower in frequency than navigation calls and they can have complex modulations in frequency that help indicate which genus and species of bat is hollering at its bat buds. We will come back to that in a bit. Finally, a feeding buzz also known as the “terminal phase call” but that sounds a little dire so, I’m just going to keep calling it a feeding buzz. Bats use this buzz to pick up close by objects when they pursue and capture prey. This buzz is made by a lot of rapid-fire calls and by “rapid-fire” I mean up to 100 calls per second! That’s so many! A lot of different species have similar feeding buzzes so unlike social calls, these aren’t useful for telling you what kind of bats are making them.

As you might imagine, recording and differentiating between calls you can’t hear might be a little like trying to hit a dartboard with a sewing needle and the dartboard is in a different room. Let me walk you through it using some examples from the 2020 Yukon Wildlife Preserve Bioblitz. During the Bioblitz, four acoustic monitoring stations were spaced out around the preserve to pick up bat calls over the span of four evening. In order to specifically pick up bat calls, the audio detectors were set to high frequencies and only recorded between dusk and dawn when bats are active. They were also set in relatively open areas to avoid noise clutter that would interfere with the recordings.

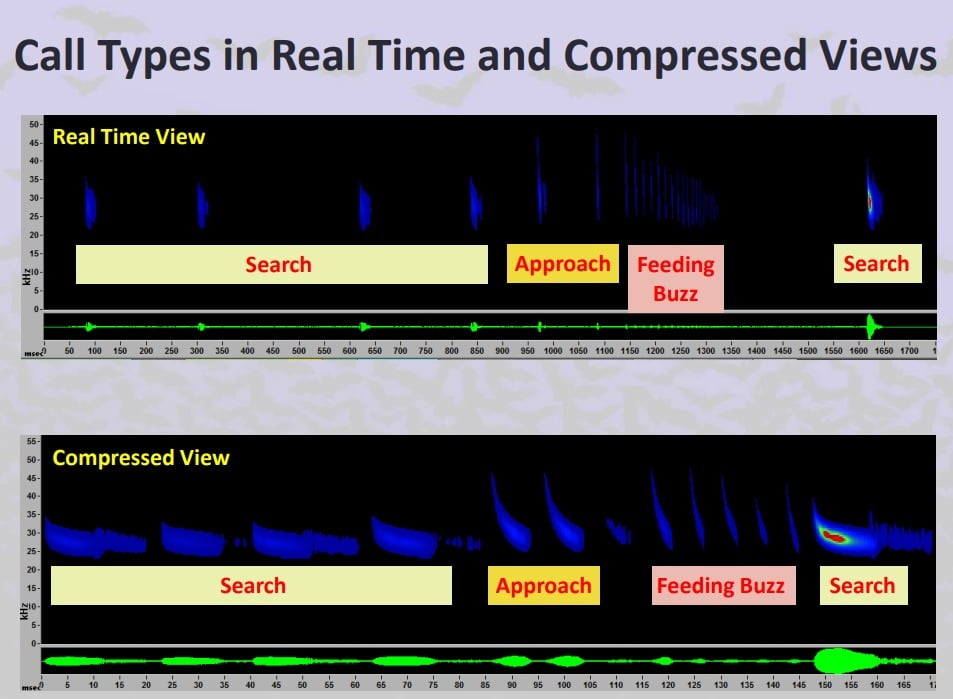

Once these calls are collected, what do you do with them? Please let me introduce you to SonoBat. While SonoBat may sound like an off-brand superhero, it’s actually software that analyses bat calls. It takes recordings of bat noises and converts them into sonograms (graphs representing sound). Sonobat lets you look at these sonograms in real-time to get an idea of the how the frequency varies across the call sequence and how much time passes between these calls. You can also check them out in “compressed view” which compresses the time interval between calls to show more details of the call at a glance. This gives you a better idea of the shape, frequency, harmonics, and relative strength of the call.

Now you’ve got all the sweet deets from your recorded bat calls, SonoBat can compare these calls to a library of calls from known bat species to help you ID which bats are in your area. However, there are similarities between the call of different bat species and not all recordings will be clear enough to make a definite ID. For example, 10% of the bat calls recorded during the Bioblitz were unidentifiable and hey, it happens. This is where knowing which bat buddies are native to your area can really help you out. Here in the Yukon, our most common tiny sky mammal is the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) but they’re not alone. The Northern bat, big brown bat, hoary bat, long-legged bat, and long-eared bat have also been spotted in the territory.

The bat calls recorded at the Wildlife Preserve Bioblitz mostly belonged to the ever-popular little brown bat (44%) while 46% was from the other bat species: The Northern bat, the long-legged bat, and the long-eared bat. We apparently have a lot of bats with lengthy body parts up here. Most of these bat calls (536 calls out of 605) were picked up by the audio recorder set up near the preserve’s pond. This makes lots of sense since a pond is essentially a bat cafeteria due the number and density of insects that like to cluster around still water.

SonoBat audio file. Thanks to Justine Benjamin for assisting in this work.

It may not be as easy as sticking your head out the door to listen to a dawn chorus of birdsong but with audio recorders, specialized programs, and some pre-existing bat knowledge you too can identify bats by their mostly ultrasonic calls! … Okay, eavesdropping on bats might not be an activity for the casual enthusiast but it’s a fascinating process nonetheless.

Joelle Ingram

Human of Many Talents

Joelle is a former archaeologist, former wildlife interpreter, and a full-time random fact enthusiast. She received her master’s degree in anthropology from McMaster University. One of the four people who read her thesis gave it the glowing review “It’s a paper that would appeal to very specific group of people,” which is probably why only four people have read it. Her favourite land mammal is a muskox, her favourite aquatic mammal is a narwhal. She thinks it’s important that you know that.

Well, I really hope more than 4 people read this as it’s really great!

Thank you, Elise! I am both glad and relieved that these articles are more fun than the 50 page technical paper that capped off my grad school years (admittedly, that’s a pretty low bar!)

Thanks Joelle, I have really enjoyed reading all of your blogs. My favorite was the one on the chickadees. You write with an entertaining style that makes something I would not normally choose to read very interesting ! I also enjoy the topics- things in our own backyard. I never thought that I would be interested in reading about bats or mosquitos.

Thanks so much, Carla! That’s exactly what we’re going for. There’s a lot of very cool things going on in your local greenbelts but information sources can be difficult to access or jargon heavy and hard to understand. This article project is essentially a handy takeout bag of fun facts to help bring people closer to the very interesting natural world around them.

And credit where credit is due, the chickadee article is courtesy of Doug Caldwell 😀