Playful Prey

Playful Prey

Taking what we know about play and what mysteries remain to be revealed in specific species, I looked at the play behaviour in mule deer fawns to see if this pattern of play behaviour mimicking antipredator behaviour held in this species of deer.

What I love most about nature is that usually our simple assumptions don’t actually hold true.

In comparison with the closely related white-tailed deer, who use their speed and agility to out-run predators and will not defend their young, the fawns of both species played very similarly, instead of matching to their antipredator strategies.5Carter, R. N., Romanow, C. A., Pellis, S. M., & Lingle. S. (2019). Play for Prey: do deer fawns play to develop antipredator tactics or to prepare for the unexpected? Animal Behaviour, 156, 31-40.

So what is happening here?

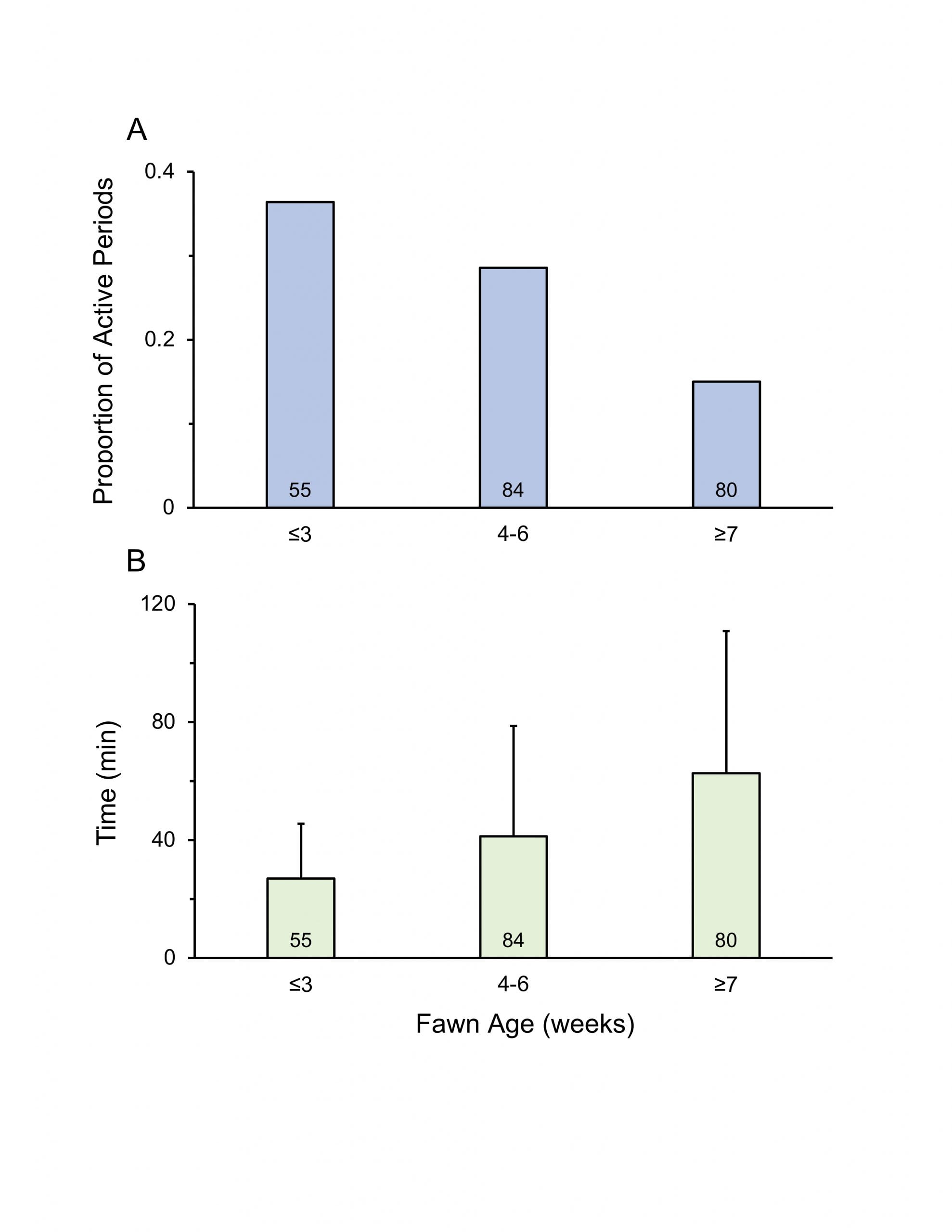

The fawns followed the timing trend with the majority of play occurring when the fawns were less than four weeks old, decreasing as the fawns got older despite becoming more active during their days overall.7Carter, R. N., Romanow, C. A., Pellis, S. M., & Lingle. S. (2019). Play for Prey: do deer fawns play to develop antipredator tactics or to prepare for the unexpected? Animal Behaviour, 156, 31-40.

Figure 1. (A) The proportion of active time in which mule deer fawns of different ages played and (B) The average duration of active time for mule deer fawns at different ages.

Mule deer fawns also liked to perform chaotic twisty and twitchy movements during play that caused them to stumble around and almost lose their balance (though in a couple of instances the fawns did fall over!). These are what are known as “self-handicapping” movements in play and are thought to help a baby animal learn the limits of their bodies and how to correct themselves when they are close to losing their footing.8Spinka, M., Newberry, R. C., & Bekoff, M. (2001). Mammalian play: Training for the unexpected. Quarterly Review of Biology, 76, 141-168.

Figure 2. Sequence of self-handicapping movements during a fawn’s play. Play Sketch based off of a video recording of play.

Another part of the brain is involved here and that is the prefrontal cortex. This region is right behind your forehead and is responsible for planning, decision making, regulating emotions, and developing social skills.9Pellis, S. M., Pellis, V. C., & Himmler, B. T. (2014). How play makes for a more adaptable brain: A comparative and neural perspectives. American Journal of Play, 7, 73-98. Animals who are not given the chance to play show an increased stress and fear response when experiencing a novel situation and have difficulty interacting with other individuals as adults. The prefrontal cortex, like the cerebellum, undergoes a lot of growth and development when an animal is young, overlapping again when animals are the most playful.10van den Berg, C. L., Hol, T., van Ree, J. M., Spruijt, B. M., Everts, H., & Koolhaas, J. M. (1999). Play is indispensable for an adequate development of coping with social challenges in the rat. Developmental Psychobiology, 34, 129-138.

Instead of mule deer fawns playing to develop their specific antipredator strategy (using a coordinated defence against predators), play may more generally improve the fawn’s overall physical and emotional resilience as they grow into adulthood, gaining and refining the skills they need for their survival. The occurrence of play directly impacting survival has been found in grizzly bears,11 Fagen, R., & Fagen, J. (2009). Play behaviour and multi-year juvenile survival in free- ranging brown bears, Ursus arctos. Evolutionary Ecology Research, 11, 1-15. feral horses,12Cameron, E. Z., Linklater, W. L., Stafford, K. J., & Minot, E. O. (2008). Maternal in- vestment results in better foal condition through increased play behaviour in horses. Animal Behaviour, 76, 1511-1518. and mountain goats 13Théoret-Gosselin, R., Hamel, S., & Côté, S. D. (2015). The role of maternal behavior and offspring development in the survival of mountain goat kids. Oecologia, 178, 175-186. with the most playful cubs, foals, and kids being more likely to survive into adulthood.

Mountain Goat kid exploring its habitat at Yukon Wildlife Preserve. The occurrence of play directly impacting survival has been found in grizzly bears, feral horses, and mountain goats with the most playful cubs, foals, and kids being more likely to survive into adulthood.

Play is such a common and well-known behaviour that we see it every day and could point it out at any given time, yet in terms of its function for different animals, it remains a complex and fascinating behaviour. We think of play as a fun and relaxing activity yet it seems to have a critical impact on an animal’s survival by facilitating the development of crucial motor and cognitive skills.

So next time you are watching your pets play in the backyard or your children roughhousing in the living room, you can think of all the complex brain and motor skill development that is happening as well!

Rebecca Carter

Senior Wildlife Interpreter

Rebecca joined the Wildlife Preserve in the summer of 2020 after moving from Manitoba to the beautiful and wild Yukon. Rebecca earned a degree in Biology with honours from the University of Winnipeg studying behaviour in mule deer (one of her top 20 favourite animals.. it’s hard to choose!). She loves connecting with others through nature and sharing stories and knowledge about the animals at the preserve with visitors.