Welcome to the Neighbourhood!

Welcome to the Neighbourhood!

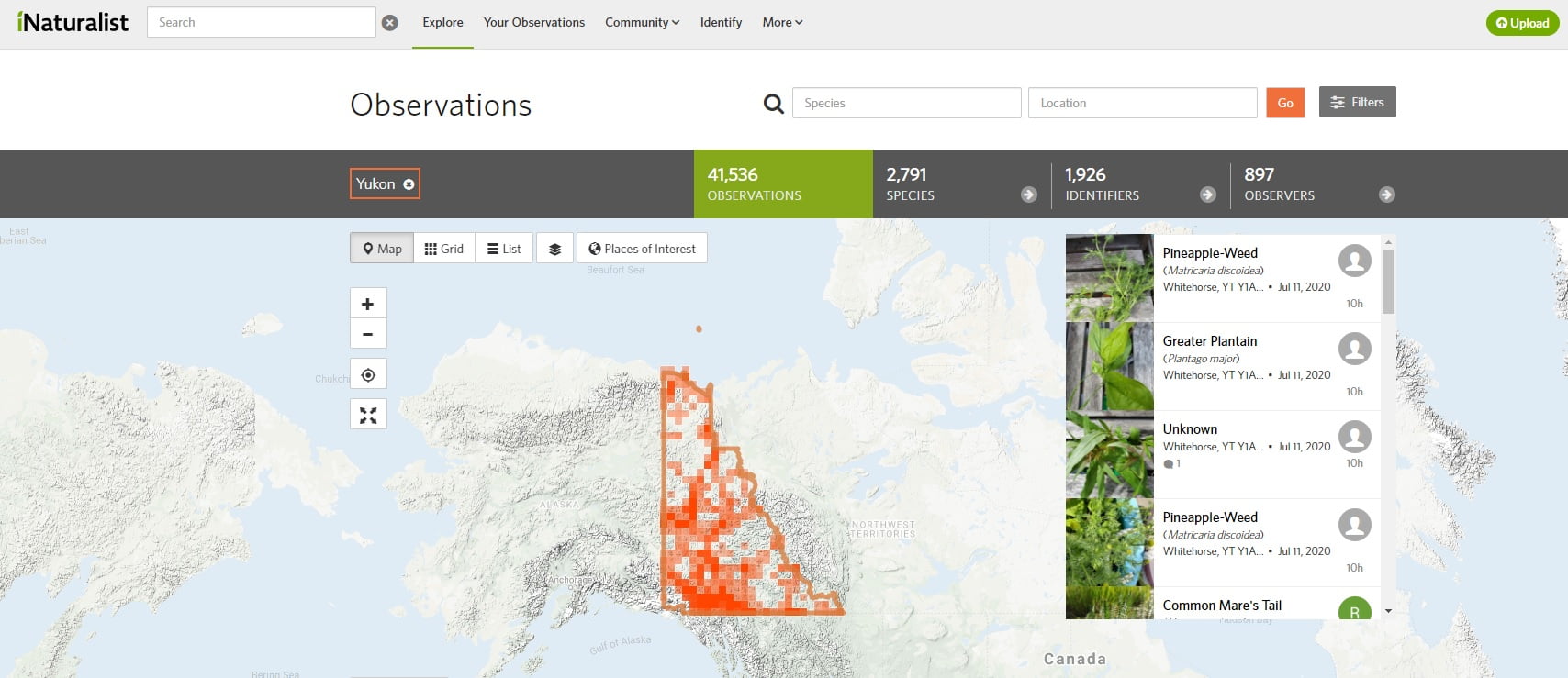

This article was made possible thanks to support from the Environmental Awareness Fund. Engage and educate yourself in this 10-part blog series, about Yukon Biodiversity.

15 minute Read

How do you feel about bats? Personally, I love bats: they’re cute and fuzzy and they eat a lot of bugs. What’s not to like? And while a lot of Yukon wildlife can be very illusive and requires patience, luck, and a lot of time in the woods to see, bats are happy to hang out in your neighbourhood so you can view them nightly as they snack on bugs. They’re very courteous like that.

In the Yukon, one bat species in particular prefers life in the city and really likes to roost in buildings. Let me introduce you to Myotis lucifugus or “little brown bat” to its friends. The Yukon’s little brown bats are very interesting: some bat species don’t do well in urban environments because there tend to be fewer insects to eat and a lot of noise and light pollution that make hunting for those bugs difficult. Bats who are used to a more natural setting can also have trouble utilizing urban roosts. Not so the case for the little brown bat. A recent study revealed that Yukon settlements are important roosting habitats for these endangered bats and they actually prefer roosting in town rather than out in the woods. But first, let’s learn more about the bats themselves.

The little brown bat is both little and brown as the name suggests; adults only weigh around 5-14 grams and have a wingspan of 25 cm. These bats have a surprisingly long lifespan for a small mammal. They can live into their 30s as long as disease or an owl doesn’t take them out. Like almost all other bats, the little brown bat is nocturnal and does all its feeding at night. Little brown bats are insectivores (they eat bugs) and they’re opportunistic feeders, meaning they eat whatever insect is available. Typically, their diet includes moths, flies, mayflies, beetles, midges, and mosquitoes and in the Yukon, they’re eating A LOT of mosquitoes. They generally have two or more rounds of feeding per night with one at sunset and the other before sunrise. In between, they’ll park themselves in a night roost to digest and conserve energy. A single bat eats half of its body weight in insects every night which means they’re consuming hundreds and hundred of bugs! They’re a very important part of the boreal forest ecosystem because they help control insect populations.

However, the good name of these little sky mice (they’re not really mice) is often besmirched because they can carry diseases. But if 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that humans do that too so let’s not hold that against bats. It can also occasionally be a bad time if they decide to set up shop in your house. In fact, the only time I did not love bats is when they were roosting in the ceiling of my cabin and a heavy rainstorm caused a waterfall of bat poo to wash down the chimney hole. Fortunately, with a little elbow grease and some strategically placed bat houses, that’s no longer a problem. More on that later (the bat houses, not the guano waterfall).

Female little brown bats usually show up in the territory during the last two weeks of April to form maternity colonies, which are made up of anywhere from a dozen to several hundred females. Just whole bunch of bat gals being bat pals. Late April in the Yukon is pretty chilly and the insects are still waking up, so the females are pretty sluggish and not very active. They’re also waking up from a multi-month hibernation so give them a break. Males show up a bit later, usually in May, and either form their own colonies or just hang out by themselves.

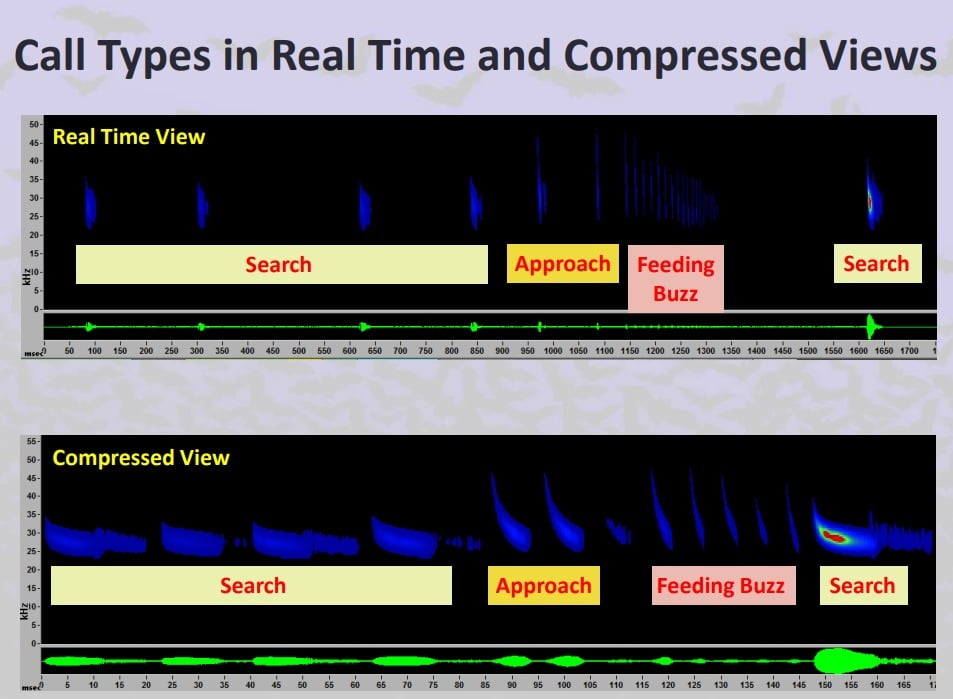

Julie Thomas sets up a detector in the feild. Learn more about bat talk in the Yukon with Joelle’s blog: How do you listen to what you can’t hear?

Little brown bats mate in the fall but fertilization doesn’t happen until spring once the female wakes up from hibernation. Gestation takes 50 to 60 days and the bat babies, known as “pups” (aw!), are born in June and July. Females only give birth to a single pup so I guess that means that every bat pup has only child syndrome (kidding, kidding).

Since there are no insects around in the winter, the little brown bat needs to build up fat reserves during the summer to carry them through the cold months. In order to conserve winter calories, the little brown bat generally go into hibernation around October or November but can go into hibernation as early as September. These little guys are true hibernators which means their metabolism, heart rate, and breathing slow to a crawl and they go into a very deep sleep. Their winter hibernation sites are usually in caves and are called hibernacula, which sounds like Dracula’s sleepy cousin. Little brown bats usually disappear from the Yukon around mid-October. There are no known hibernacula in the territory and it’s suspected that hibernation happens elsewhere. Bats can migrate hundreds of kilometres between roosting and hibernation sites so the Yukon populations likely winter in known hibernacula in Prince of Wales Island in southeast Alaska (400 km south of the Yukon) or possibly Wood Buffalo National Park, Alberta (500 km east of the Yukon). Strangely enough, the reason bats leave the territory in the winter isn’t because we don’t have caves (we do), or because of the cold (although that would be understandable). It’s likely they don’t stick around because it’s too dry. There is so little moisture in our winter air that bats could die from dehydration while hibernating and that would be a real bummer.

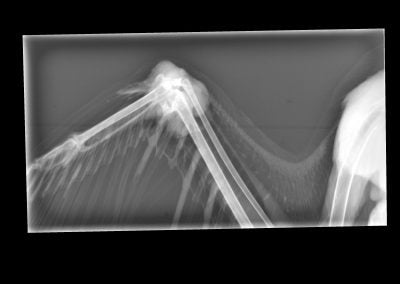

A harp net trap is used capture bats without exposing them to disentagling. This harp net is set up at the base of the Squanga Lake bat house to capture bats exiting at dusk. Photo credit: Justine Benjamin

Little brown bats are habitat generalists meaning they can live in a variety of different places and this flexibility is why they do so well in urban environments. They form their roosts in tree cavities, under tree bark, in rock crevices, caves, and, of course, man-made structures. Little brown bats tend to forgo the tree option in the Yukon as the trees are too small to host large maternity colonies. Bat home-hunters are looking for dead trees with trunks that are at least 40 cm in diameter that get a lot of sunlight to keep them nice and toasty during their day snooze. As you might imagine, the asparagus-esque trees of Yukon don’t offer many candidates that tick all these boxes, so the little brown bat sets it sights on that sweet suburban life.

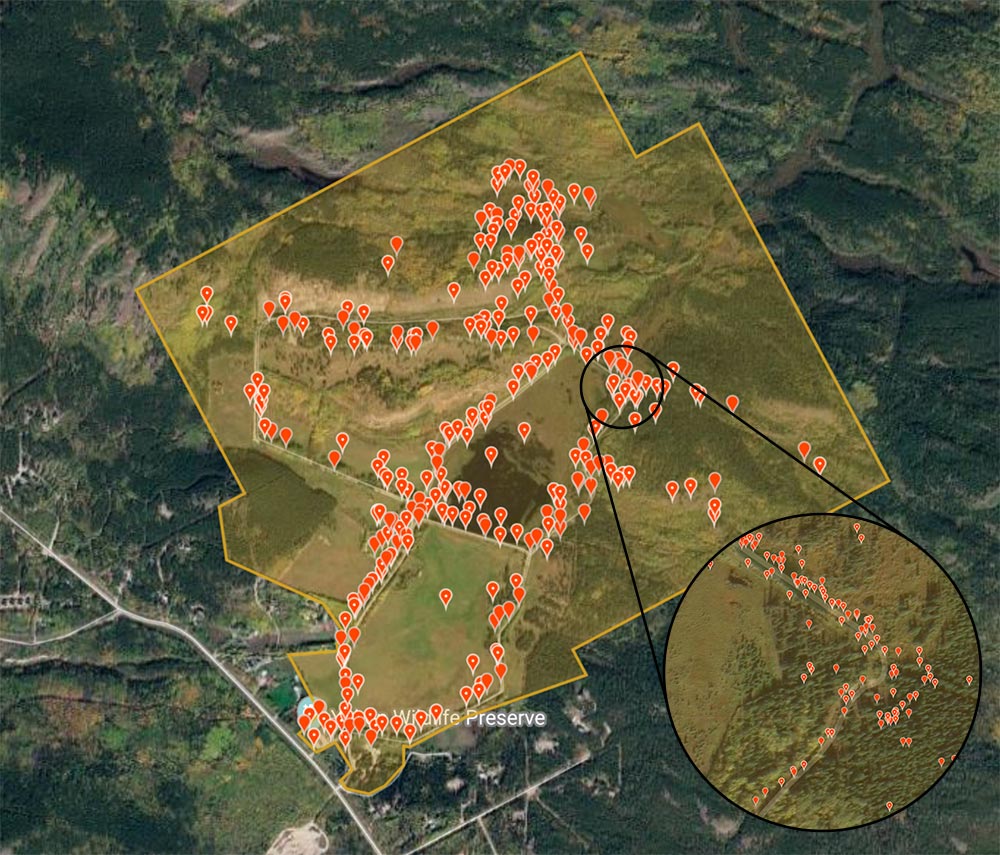

Because of their habitat choice, the Yukon’s little brown bats are considered synurbic. The term “synurbic” is fun to say out loud and refers to animals that are more abundant in urban centres than they are in the surrounding forest. The rapid expansion of human settlements is a major conservation issue because it infringes on the natural habitat of many different species of animal. Fortunately, little brown bats are apparently the embodiment of “Improvise. Adapt. Overcome.”, and they are doing quite well in their northern urban environment.

A recent study conducted around Carmacks, Haines Junction, and Teslin noted that the little brown bat colonies in these areas were concentrated around the rural villages. The advantage of small towns over large urban settlements is there is a lot less light and sound pollution. Buildings also make excellent roosts; they give females a cozy place to raise their pups and can actually lead to faster growth rates in their young. Bats can also take advantage of the linear, open corridors created by roads and hydro lines for energy efficient commuting and foraging. Flight is exhausting and bats have very few hours of darkness to eat a lot of bugs so they need all the help they can get.

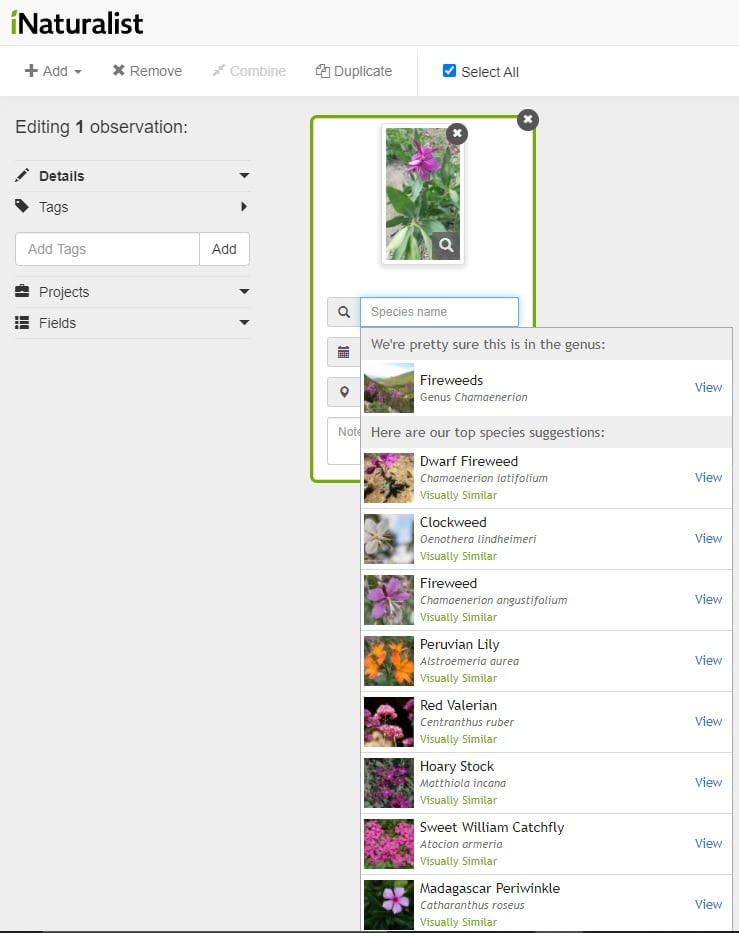

Photo credit: camerondeckert iNaturalist

Where are these little bats flying off to? If towns are for bat apartments, then wetlands and old forests are bat grocery stores so naturally, little brown bats prefer buildings near some form of wet. While people places offer an ideal nap zone, there is a better bug density elsewhere. When bats need a snack, they head for wetlands, swamps, or mature forest. Young forests can be too cluttered but older forests have the open areas these bats crave. Less obstacles, easier travel, baby! Also, if you have ever had the dubious privilege of hanging out around a swamp at any time of day, you will know that if bugs were a large component of your diet, you would be very full.

Despite the people houses and the wetlands, at first blush, the Yukon doesn’t seem like the ideal environment for bats. They have to contend with colder temperatures and limited bug availability at the beginning and end of their foraging season. The extended summer daylight hours in the Land of the Midnight Sun limits their nighttime activity periods. So why does the Yukon have a healthy little brown bat population while their numbers are in decline all across the continent? Well, things are about to get sad.

Habitat destruction definitely has a negative impact on bat populations, but bats are also dealing with a plague of their own. White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a disease caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans that grows on bats as they hibernate in caves. The fungus appears as a white fuzz on the nose, wings, and ears of hibernating bats. It damages muscle tissue and blood vessels and causes bats to dehydrate by sapping water and electrolytes from their wings. Bats afflicted with the fungus will become more active and wake up too frequently during hibernation meaning they’ll burn through their fat stores too quickly and will have no way to replenish them. Essentially, WNS causes bats to starve to death.

Since WNS showed up in North America in 2006, it’s killed off millions of bats and caused steep declines in the bat populations of eastern Canada. It’s making its way across to the western half of the country but it hasn’t made it up to the massive boreal forest that makes up northwestern Canada which makes it an important conservation area for this rapidly disappearing species. Especially so as the microclimates of the boreal forest may be unsuitable for the growth and spread of the fungus responsible for WNS.

While we’re in the neighbourhood, let’s keep getting depressing. Bat populations do not recover quickly if they do recover at all. They’re sensitive to environmental change (and face fungus) and with one pup per female per year, it’s slow to rebuild lost numbers. With this in mind, preserving existing bat populations is a more sure-fire method of conservation than trying to rebuild them.

Alright, enough with the sad, onward with the hopeful. There are a bunch of ways that you and I and all Yukon residents can help our bat neighbours. First and foremost, protecting wetlands and ponds, especially those near residential areas, is important not only for keeping bats fed, but also for frogs and aquatic birds. It’s also important to provide them with a safe and accommodating roosting area. There are some great benefits to having bats living in or around your home and many people live comfortably with bats roosting in one of their buildings. They snarf up a lot of the bugs that haunt you during the summer and their guano is fantastic for fertilizing gardens.

However, as I mentioned earlier in the article, sometimes having bats roosting in your roof can sometimes lead to guano geysers hosing out of your ceilings and that’s not great (admittedly, those were some extreme circumstances). If you need to relocate your bat roomies, you need to do so carefully. First, have an alternative roost available. You can purchase a bat house at http://canadianbathouses.com/ or, if you’re feeling crafty, you can find instructions to build your own online (https://yukon.ca/en/building-yukon-bat-nursery-house). You may have to wait until the bats leave in the fall/winter then block the cracks and crannies they use to enter your home. This will encourage them to move to their new roost when they show back up in the spring! It’s important that you don’t block gaps that bats use to enter and exit your home during the summer months when bat pups will get trapped inside. For details on how to comfortably co-exist with your new bat neighbours and report your bat sightings to batwatch@gov.yk.ca to help with continued bat research!1https://yukon.ca/sites/yukon.ca/files/env-bats-buildings.pdf

The boreal forest is at the northern edge of the little brown bat’s range which means there’s less chance of them interacting with bats that have been affected by white-nose syndrome. Although the trees are too thin and the winters are too dry, human settlements provide essential roosts that the Yukon’s forests can’t deliver and our wetlands are a deluxe buffet for insectivores. Preserving Yukon wetlands and waterbodies and being kind to your little winged neighbours plays an essential role in preserving the endangered little brown bat. Also, it would be super cool of you.

Joelle Ingram

Human of Many Talents

Joelle is a former archaeologist, former wildlife interpreter, and a full-time random fact enthusiast. She received her master’s degree in anthropology from McMaster University. One of the four people who read her thesis gave it the glowing review “It’s a paper that would appeal to very specific group of people,” which is probably why only four people have read it. Her favourite land mammal is a muskox, her favourite aquatic mammal is a narwhal. She thinks it’s important that you know that.