The Early Years

The Early Years

This article was made possible thanks to support from the Yukon 125 Fund. Learn the incredible history of the Yukon Wildlife Preserve, and Yukon Game Farm from the people of the past through this series of articles.

This article was made possible thanks to support from the Yukon 125 Fund. Learn the incredible history of the Yukon Wildlife Preserve, and Yukon Game Farm from the people of the past through this series of articles.

Danny Nowlan is one of Yukon’s colourful, and at times, notorious characters. He was a polarizing figure who cared deeply for animals and connecting them to kids. He was also the subject of one of Yukon’s most expensive trials ever. His work on the Yukon Game Farm would eventually result in the creation of the Yukon Wildlife Preserve. That is a legacy that is still experienced by many Yukoners – although many of the stories are not known or well understood.

The stories of Danny Nowlan are important threads that are woven through the tapestry of Yukon’s recent history. This project gives us the opportunity to capture and share this history before its lost. This includes the opportunity to celebrate the positive lasting legacy and to learn about and grapple with the challenging aspects of this legacy.

In 2023 historian Sally Robertson collected oral histories from more than a dozen people who knew Danny. Out of this work, Sally wrote a series of stories about Danny and his adventures.

(6 minute read)

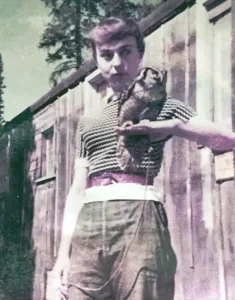

Erika Nowlan. Photo gratefully provided by Sabrina Nowlan.

Danny Nowlan and his first wife, Erika, bought the land that eventually became the Yukon Wildlife Preserve in 1963. In typical Danny fashion, the purchase was less than straightforward and contained details useful to a talented story-teller – as Danny was. Harry Gordon-Copper owned the Hot Springs, and he owned this land – a place where White Pass and Yukon Route pastured their horses in the early 1900s. Erika sold her house in Whitehorse for some cash, and they gave Harry a stereo system purchased and kept from their previous business running the White River Lodge on the Alaska Highway. They had the land but no money to develop it, so Danny got a grazing lease west of the Hot Springs and started raising horses to sell to the outfitters.

Danny and Erika dreamed of developing a place where northern animals were shown in a home-like environment for educational and conservation purposes. Danny had a way of understanding wildlife that astounded those who knew him. He had a reputation as an expert in training eagles and falcons, and the wolf he raised at White River was the topic of a magazine article.

Wolfy Article – The Star Weekly Magazine, October 17, 1959

This wolf gives the lie to legends by Hugh M. Halliday.

Like the time he brought a little Porter locomotive from an abandoned railway near Dawson. He thought a little steam train could carry people around the property, and the kids would love it. He took his 5-ton vehicle up to Dawson to pick up the more than 10-ton locomotive. It was a wild ride to Whitehorse, with Danny running the truck into snowbanks along the road to slow the vehicle. The truck’s brakes were not up to the job and by the time they reached Whitehorse they were burned out. Danny always had big ideas, and he usually backed them up with detailed and practical plans. The little railway did not pan out.

When the Nowlans purchased the property, it had a variety of high and low land, but the central feature was a wetland where today there is a big field. The property needed roads and trails to be accessible for visitors and, although the marsh attracted wildlife, it was not part of Danny’s vision. At a local auction, he picked up a large earth mover (“scraper”) and a D8 caterpillar tractor with a cable-controlled blade (“cable cat”). This machinery was difficult to operate but it would be instrumental in building roads through the property – and Danny had a bigger plan than just roads.

He built a dam across the drainage from the cliffs to dry out the wetland and create a pasture for first mule deer and later bison. A pond developed behind the dam, and it attracted migratory birds and small mammals. The small animals attracted fox and coyotes, so the next step was fencing. He used whatever came to hand, including 3” pipe from the CANOL pipeline, an ill-fated World War Two project. He put a fence around an area with a small herd of grazing mule deer, and the Game Farm had its first large residents.

Some of the early buildings on the Game Farm were interesting. Danny bought the Yukon’s first airport hanger and moved it out to his property. His daughter Peregrine remembers two baby bears living under it. The Nowlans’ little home by the road did double duty as an animal hospital as Danny brought in wounded and abandoned animals. An owl with a broken wing was put in Erika’s book room and it roosted there on a shelf. She was forever cleaning owl poop off her books. A baby mink always wanted to swim. He joined the kids at bath time, and he developed a terrible habit of swimming in the toilet bowel if someone left the lid up at night.

Sabrina Nowlan with a Dall lamb. Danny’ and Erika’s second daughter, born 1965 and lived 17 years on the farm and in Whitehorse. Photo provided by Sabrina Nowlan.

One night Erika screamed and woke the kids because a wet mink was running around inside her sleeping bag. She loved animals and endured a lot of chaos. Like the time Danny put their four-year-old daughter Sabrina astride a moose called Susiecue. The moose took off, and Danny was yelling for it to come back and shaking a bucket of oats. Sabrina went for quite a ride and remained completely fearless. Erika was not impressed.

Dall’s sheep were to be the Game Farm’s main attraction. They are magnificent creatures, they can be difficult for the ordinary person to see in the wild, and there was a market for them in southern zoos and game farms. After obtaining the necessary permits, a crew of hardy folk set off to capture some breeding stock at Thechàl Dhâl (Sheep Mountain) near Kluane Lake. Danny’s kids, Peregrine and Sabrina, looked after those first little lambs and kept them in their bedrooms. Wildlife biologist Manfred Hoefs was in the capture group. At that time, Manfred was a graduate student studying Dall’s Sheep horns. Danny, who had a Grade 2, a Grade 3, or a Grade 6 education (depending on who he was talking to), was famous for the amount of research he did on animals and their habitat. He was also famous for the number of useful contacts he developed with experts in many fields. Manfred continued to visit the sheep on the Game Farm for many, many years and established a Dall’s Sheep horn measuring protocol that the Yukon Wildlife Branch used to build a valuable and still-used research dataset.

Sheep camp for sheep capture – from left to right: Unknown, Teddy Yardley, Herb Zollweg, Unknown, Unknown, Danny Nowland and Erika Nowlan

All of Danny’s friends enjoyed a good story, and one of them involved the Game Farm sheep and the road building equipment. Danny was never very careful with equipment, and the machinery ended up sitting in the sheep enclosure. Manfred came to the Farm one time and found the rams all lined up and running at one of the scraper’s huge tires. They would bang into the rubber, bounce off, and run at it again. Manfred said they were loving it – the best thing they had ever hit in their lives. They just kept going – bang, bang, bang. Sort of like Danny – living and loving life to the fullest.

• • •

Photo gratefully provided by Uli Nowlan unless otherwise noted.

Sally Robinson, October 2023

with words from interviews with Peregrine Nowlan, Sabrina Nowlan and David Mossop.

Sally Robinson

Vintage Ventures - Researcher & Writer

Lindsay Caskenette

Manager Visitor Services

Lindsay joined the Wildlife Preserve team March 2014. Originally from Ontario, she came to the Yukon in search of new adventures and new career challenges. Lindsay holds a degree in Environmental Studies with honours from Wilfrid Laurier University and brings with her a strong passion for sharing what nature, animals, and the environment can teach us.