JB the Moose

JB the Moose

6 minute read

On August 15th 2024 the Preserve’s Animal Care team with the support of one of our veterinarians’, Dr. Julianna Campbell made the difficult decision to say goodbye to JB the moose. Her condition had declined rapidly over the last 6 weeks when our team noticed she was starting to look thin. She developed diarrhea which dramatically impacted her body condition. She had lost a significant amount of weight (she was estimated to be 200-300 lbs under her normal weight). Unfortunately in that time, physical exams and fecal / blood tests did not reveal the cause. Nor did she respond to attempted treatments. Despite enthusiastically eating browse, our Animal Care Team was seeing her increasingly displaying signs of distress or pain. She also now lacked the body condition to handle colder winter temperatures (and now the ability to regain the necessary body condition in the next couple of months). In order to mitigate her suffering we made the decision to euthanize her.

JB the moose. Summer 2024. Photo credit: Melissa Mark

The morning of the 15th, after she was immobilized the euthanizing drugs were administered and she passed away quickly and easily. Our Animal Care Team conducted a necropsy which includes a physical exam of the internal body systems as well as taking a series of tissue samples that will be sent out for testing. The goal is to understand the root cause of her sudden decline in health. Very preliminary necropsy results show hemorrhaging / ulcers in one of her stomachs and intestines, but understanding why will be more challenging. Once we have more information and a better understanding of what happened, we’ll share more information. Testing of samples can take several weeks, so we won’t know right away.

JB the moose. Winter 2016. Photo credit: Jake Paleczny

JB was well known to many visitors over the years. She was generally calm mannered and smaller than the other female moose, Jesse, who was 2 years younger than JB. Jesse has been known to have a lot more attitude and dominant behaviour.

JB arrived as an orphaned moose in spring 2014. Orphaned moose are notoriously difficult to hand raise and we hadn’t received an orphaned moose in many, many years. Under Dr. Maria Hallock, the Animal Care Team threw themselves at the situation – feeding every 3 hours at first, spending nights with her, etc.

JB the moose First Day. She arrived May 26th, 2014. Photo credit: Justine Benjamin

In a near-tragic twist, JB broke her leg. Although it might have been the end for any other moose, Maria put a cast on JB’s leg. Because JB was growing so quickly the cast had to be cut off and redone just 2 weeks later, but eventually the cast came off.

The Animal Care Team put in a huge effort that spring. Among others, Dr. Julianna was at the YWP as a summer student in 2014 and was part of the team that bottle raised JB.

Another person on the team that year was Justine Benjamin. Justine spent more time than anybody else with the young moose, right through to when she was moved into the main habitat in February 2015.

Because of that special connection and dedication from Justine, Maria proposed we name the moose JB. Justine is now a part of our Board of Directors and Chair of the Animal Care Committee.

At that time we didn’t have a laser therapy machine (for reducing inflammation) but All Paws Vet Clinic and their team continued their support of the moose, bringing out their machine for regular treatments. Further, we received support for a local physio therapist, Natasha Bilodeau after the brace was off to help continue the healing and recovery. Normally we’d be starting to decrease our time spent with a calf, but with the cast leg she continued to need a lot of support.

Later in the winter she was introduced into the main habitat with our bull moose. Years later as Jesse joined the group, the three of them roamed the 40 acre moose habitat.

• • •

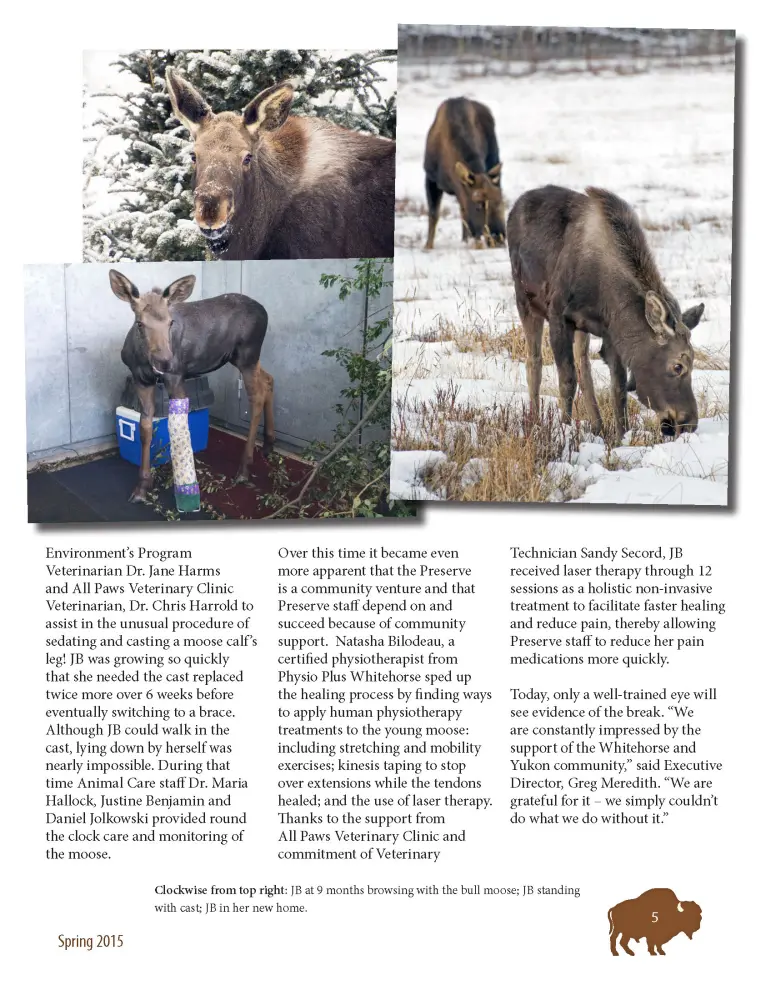

The following is an article created in our original newsletter, the Preserve Post in Spring 2015.

• • •

The Yukon Wildlife Preserve is a zoological institution and a non-profit charity dedicated to connecting our visitors with the natural world. As ambassadors of the Yukon Wildlife Preserve’s animals, lands, and operations, the operating society proudly maintains populations of 10 species of Yukon wildlife in large natural habitats. The society also conducts educational programming and funds a wildlife rehabilitation program for Yukon’s injured and orphaned wildlife. The facilities and the level of care provided to the Preserve’s animals successfully meets the stringent criteria of Canada’s Accredited Zoos and Aquariums, to which the Yukon Wildlife Preserve is a long-time member.

Lindsay Caskenette

Manager Visitor Services

Lindsay joined the Wildlife Preserve team March 2014. Originally from Ontario, she came to the Yukon in search of new adventures and new career challenges. Lindsay holds a degree in Environmental Studies with honours from Wilfrid Laurier University and brings with her a strong passion for sharing what nature, animals, and the environment can teach us.

Jake Paleczny

He/Him - Executive Director/ CEO

Jake Paleczny is passionate about interpretation and education. He gained his interpretative expertise from a decade of work in Ontario’s provincial parks in addition to a Masters in Museum Studies from the University of Toronto. His interests also extend into the artistic realm, with a Bachelor of Music from the University of Western Ontario and extensive experience in galleries and museums.