Wandering Wood Bison

Wandering Wood Bison

7 minute read – “Winter Is Here” series continues with the true behemoth of the north – Wood Bison!

At first glance, the Wood Bison (Bison bison athabascae) seems to be ill-suited to live in the far North. Especially when we think about its Southern cousin, the Plains Bison (Bison bison bison), which historically has made its home on the rolling hills and endless grasslands of the prairies. It seems fairly safe to assume that compared to the prairies, it is a completely different game of horns to survive the winter in the Yukon. Extended periods of extreme cold, a short growing season – hence relatively scarce food sources, combined with unforgiving, mountainous and swampy terrain pose a different set of challenges. Yet bison are thriving – how do they do it? Through a series of adaptations in structure, behaviour and physiology, we will see that Wood Bison are in fact quite at home in the far North.

The Wood Bison is a giant: the largest living land mammal in North America. Males can weigh up to 2000 pounds, which is up to 30% larger than its Southern relative; * roughly * the difference between a SmartCar and a VW Golf. In colder climates it actually pays to be bigger! Larger individuals (which have a smaller surface area-to-volume ratio) are better at retaining heat. This rule of nature is known as Bergmanns Rule. A pattern, where species tend to be larger in colder climates than similar species of the same genus living in warm climates, is certainly not law – not all species of nature comply with it. Yet, bison do, and living large in a cold climate means the more fat you can store to help you get through winter. 1[Read more about the complexity of nature pertaining to Bergmanns Rule

Two Wood Bison bulls at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve. Take note of the large shoulder hump and the massive head and broad face.

Beyond size, additional adaptations assure the success of Wood Bison including a very thick and woolly winter coat. This extremely dense coat of durable hair is so warm, combined with that retained body heat, and incredibly thick skin, falling snow that accumulates on its coat does not melt, thus keeping them dry and warm.

Foraging for food in the winter is a challenge – summer vegetation is buried in deep snow and is of low nutritional value. Wood Bison “dig” for food by swinging their large, heavy heads. Within that big hump on their shoulders are long spines on the vertebrae, muscles and ligaments which support large neck muscles and the head. Now you know – that big odd hump on their shoulders is not just fat – it is a vital tool for their survival.

To manage decreased food availability and quality bison cannot just simply eat more food, more often, to sustain itself. As an ancillary adaptation, and most fascinatingly, Wood Bison are able to slow their metabolism during winter as a way to conserve energy. Just like cows, grass is a bison’s staple food in the wild but it does not contain many nutrients in the winter. By slowing down their metabolism it also slows down digestion, thus the food is kept longer in the intestinal tract which allows them to draw more energy out of one feeding. Rather than putting out critical energy by digging through snow (with their giant head!) and foraging for food, they can instead conserve energy by slowing their metabolism and getting more available nutrition from one feeding. This slowed digestion is doing double duty for the bison. As they are able to squeeze every bit of nutrients from a feeding this anatomical process is also producing valuable internal body heat.

In the Yukon landscape, Bison have been roaming for millennia; first as the Steppe Bison, predecessor to the Wood Bison. Due to a number of reasons however, they became extirpated in their Yukon homerange in the early 1900’s. It is believed it may have been a combination of habitat loss due to climate change, disease and human predation. In the 1980’s, the Yukon Government joined the National Wood-Bison Recovery Program and re-introduced a herd of about 170 bison. Since then, Yukon’s wild Bison have re-adapted to life in the North – quite well too! Making best use of their terrain, they seek shelter in treed valleys when the weather gets nasty. Interestingly, they can also be found on alpine plateaus up to 5000ft. High altitude meadows are exposed to wind, which reduces the snow cover and allows the bison to find the underlying grass more easily. Typically good habitat for bison; however when winter weather patterns swing it can add additional challenges to these food driven behemoths. A sudden warming in the winter of 2018 caused peril for a few of these wandering bison. 2An odd case of bison death in the Yukon

Consciously or not, wood bison may make use of a weather phenomenon that sometimes occurs when temperatures drop: the inversion layer. Under some conditions, a layer of cold dense air accumulates in the valleys and without wind, may stay there for days. Meanwhile, on the mountain tops the air can be up to 20C degrees warmer – well worth undertaking the climb. One could argue, with all science put aside and simply as the Kings and Queens of living large, they might like to hang out on top of their kingdom. If this was me living out there, that’s what I would do!

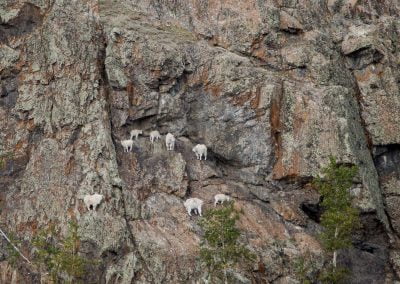

These mighty large creatures might seem fairly sedentary but their numbers have grown strong and steadily since re-introduction. They have proven their adaptability to varying habitat; moving among forested stands and meadows, alongside caribou and moose, to wandering hill-side, among mountain sheep. They are a formidable ungulate, and one of the most, among the prey animals in the Yukon. Their massive size and mass consumption of greens is not to be mistaken for sluggish or unresponsive carriage. Wood Bison are intelligent animals that are quick on their feet when needed. Their ability to outrun predators such as wolves or humans is unprecedented. These monumental animals could quickly leave you in the snow-dust as they purposefully trek their northern landscape in order to thrive.

Sarah Stuecker

Wildlife Interpreter

As a wilderness guide, Sarah has spent many days out in the bush over the years. Sitting out there glued to the scope is just as fascinating to her as observing and following animal tracks in the depth of winter, trying to draw conclusions of what this particular critter might have been up to. Sarah is passionately sharing her stories as part of our team of wildlife interpreters.