How are Animals Named?

How are Animals Named?

Throughout history, various languages and cultures have contributed to a wide – and often confusing – vocabulary used to describe animals’ genders, the young stages of their lives and what they may be called when they are gathered together in groups.

Mule deer:

Males are called bucks. Females are called does & young are fawns.

A group of deer are often called a herd but more fun versions include a bevy, a bunch, a rangale or a parcel

– though a parcel is often in reference to a group of young deer.

Historically, adjectives were the labels of choice to communicate animal gender identifiers. A broad selection of these labels has resulted – which are not universally applied, even within the same species. For example: in the deer family or Cervidae, males are identified as bucks and females are called does. In moose, and caribou – also members of the Cervidae family – males are called bulls and females are called cows while elk males are referred to as stags.

Cervids

From left to right – moose, caribou and Elk.

Males are called bulls (elk are called stags) and females are called cows.

Generally these cervids in groupings would be called herds (though moose are not actually herd animals) while elk can be also called a gang – watch out!

Not limited to just fur-bearing creatures, these titles are applied to other species and there are often departures from the naming conventions used. Rabbits are called bucks and does while steelhead trout males are called bucks, with females being called hens rather than does.

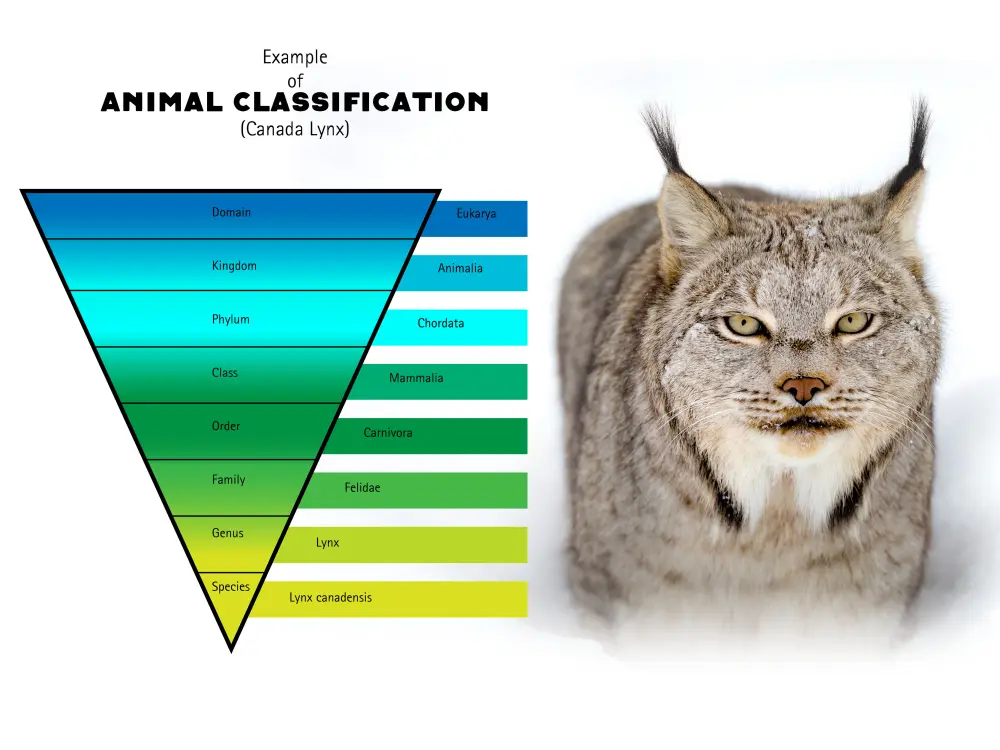

There is also a vast difference in the scientific naming of all creatures. Over the centuries a number of early scientists attempted to establish a format to classify animal groups. Ancient Chinese created the first recorded reference in 2700 BC, but it was quite limited and focused primarily on flora (vegetation) of their geographic region.

- Remember Fox and the Hound? A male is called a tod (sometimes a reynard or a dog), while females are referred to as vixens.

- Young are most commonly called kits but can also go by cubs, or pups.

- The collective noun to describe a group of foxes are a skulk, earth or a leash! These names are related to fox behaviour corresponding respectively as a group hunting together, a mama fox with her kits, and a group of domesticated or captive foxes as a leash.

Now, there are other foxes including Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), swift fox (Vulpes velox), fennec fox (Vulpes zerda), and others across the world for a total of 12 species that comprise the largest genus, Vulpes.

Smaller classifications exist within the genus Urocyon which include the gray fox. The only extant species of fox belonging to the Otocyon genus is that of the bat-eared fox found in the African savanna.

Ancient Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle described a large number of natural groups, and although he ranked them from simple to complex, his order was not an evolutionary one. He was far ahead of his time in separating invertebrate animals into different groups and was aware that whales, dolphins, and porpoises had mammalian characters and were not fish. The Aristotelian method dominated classification for many centuries. During this period, it provided a procedure for attempting to define living things through careful analysis, it neglected the variations between living things.

In 1758 Carolus Linnaeus, who is usually regarded as the founder of modern taxonomy and whose books are considered the beginning of modern botanical and zoological nomenclature, drew up rules for assigning names to plants and animals. He was the first to use binomial nomenclature consistently. Although he introduced the standard hierarchy of class, order, family, genus, and species, his main success in his own day was providing workable keys, making it possible to identify plants and animals from his cataloging. Linnaeus was the father of the Field Guide.

Over the centuries a number of paleontologists, biologists, and scientists contributed to refining Taxonomy as we know it today. Perhaps the most notable of these was Charles Darwin – who explained his theory of evolution by describing how animals changed over time, yet still remained within specific categories in taxonomy.

Below is a table defining each classification of steppe Bison, the 15,000-year-old ancestor of today’s wood bison. As you can see, their classifications are not much different, other than identifying wood bison as a sub-species.

While their scientific classifications are very similar, the animals themselves were quite different. Steppe bison persisted through the great extinction of the last Ice Age up until about 5,400 years ago. A relatively recent find in Whitehorse city limits proves steppe bison persisted giving rise to the bison seen in the Yukon today but are not the direct descendants of the steppe bison.

Darwin’s famous illustration The Tree of Life displays the evolutionary relationships between species. This idea caused a great deal of controversy when he concluded that mankind evolved from the apes which was contrary to the religious teachings of the day.

Muskox and bison – both species are members of the Bovidea family. In this family, males are called bulls and females are called cows. The young are called calves and groups of both species are referred to as “herds”. But that is where the line is drawn for their nomenclatures. The Inuit name for muskox is “omingmak,” which means “the animal with the skin like a beard.” Geographically, today’s populations of muskox and bison do not overlap and their adaptions to winter survival as a result are very different.

We can see from this phylogenetic tree how bovids (horn bearing) and cervids (antler bearing) are related to each other. The animals with icons represent those species at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve. The Yukon has 9 of the 11 ungulates of North America, excluding the bighorn sheep and pronghorn antelope. What’s also interesting to note is that mountain goats are their own genus and muskox are more closely related to sheep and goats than they are bison!

When we dive into the scientific name we can see how the classifications carry over. For instance muskox, Ovibos, share genus naming from sheep and cow. Caribou or Rangifer tarandus is reindeer in Latin, from the Greek tárandos, also meaning reindeer. So when someone asks you the difference between caribou and reindeer, you can say, nothing! (Except, reindeer fly!)

(Note: this a general phylogenetic tree; it is not complete and does not represent accurate branch length for amount of genetic change and complexities of sub-taxa).

Beyond the labels used for animal species, their offspring also suffer from a variety of descriptors to classify their young age. There are calves, fawns, foals, pups, cubs, kittens, chicks, hatchlings, fry and owlets to name a few. Yes, there is a lot to remember, but with practice you can master the various names used to identify animal difference.

These descriptor variations also extend to the words used to describe a group of an individual species. There are herds, colonies, congresses, tribes, swarms, flocks, droves, clutches, packs, murders, litters, pods, braces, convocations, gangs, schools, hordes, gaggles, bands, and numerous other words used to describe a group of same-species creatures. There are even names given to groupings of animals that are, in fact, unlikely to group together given their territorial and/or solitary nature – like owls, moose or wolverines.

Even within a class of animals like birds, its a complex web of classification and further to each species’ grouping names.

Birds:

|

Other mammals:

Invertebrates:

Amphibians (no reptiles in the Yukon):

Fish:

|

It’s an interesting read to understand the many different words used to describe an animal’s gender, how they are identified when they are youngsters and in groups together. Of course, the list above is centered on animals that make their home in the Yukon – imagine some of the animals that live in your neck of the woods, or places you’ve travelled to, and what those animals’ naming classifications may be.

What is more, the naming of animal’s as described by history must also recognize that many of these species, (beyond the few mentioned like Wapati and Omingnak), also hold Traditional and First Nation naming of animals that are descriptive, communicating the animals’ place, use or spiritual significance.

Do you have any interesting or favourite animal classification terms/names? Share them with us in the comment section below!

Doug Caldwell

Wildlife Interpreter

Doug is one of the Interpretive Wildlife Guides here at the Preserve. An avid angler and hunter he has a broad knowledge of Yukon’s wilderness and the creatures that live here. With a focus on the young visitors to the Preserve, Doug takes the extra time to help our guests to better appreciate the many wonders of the animal kingdom here in the Yukon.

Lindsay Caskenette

Manager Visitor Services

Lindsay joined the Wildlife Preserve team March 2014. Originally from Ontario, she came to the Yukon in search of new adventures and new career challenges. Lindsay holds a degree in Environmental Studies with honours from Wilfrid Laurier University and brings with her a strong passion for sharing what nature, animals, and the environment can teach us.