How Do Animal Communicate?

How Do Animal Communicate?

20 minute read –

How Animals Talk: An Introduction

All creatures communicate with one another and others by using the primary methods of sound, sight, touch, body language (visual cues) and scent.

The Limits of Human Senses

Some of these communications methods are not as pronounced for we humans as we did not evolve the superior abilities with our senses to make a living on the landscape and protect ourselves, we evolved the big brain instead. Humans are not physically equipped to detect the many subtle elements within a particular scent or distinguish all individual scents that may be present at a common location. Our olfactory systems are not that well developed. Our hearing range is also limited in comparison to various species that can hear much higher and lower frequencies than average humans. So too our vision abilities where animals have some very envious advantages with their eyesight. Some animals can easily see in the dark, some can see greater distances than us, while others can see colours beyond our range of vision – some into the infrared portion of the natural light spectrum. One can only imagine what insects perceive with their Arthropod or compound eyes.

Sound: Nature’s Symphony

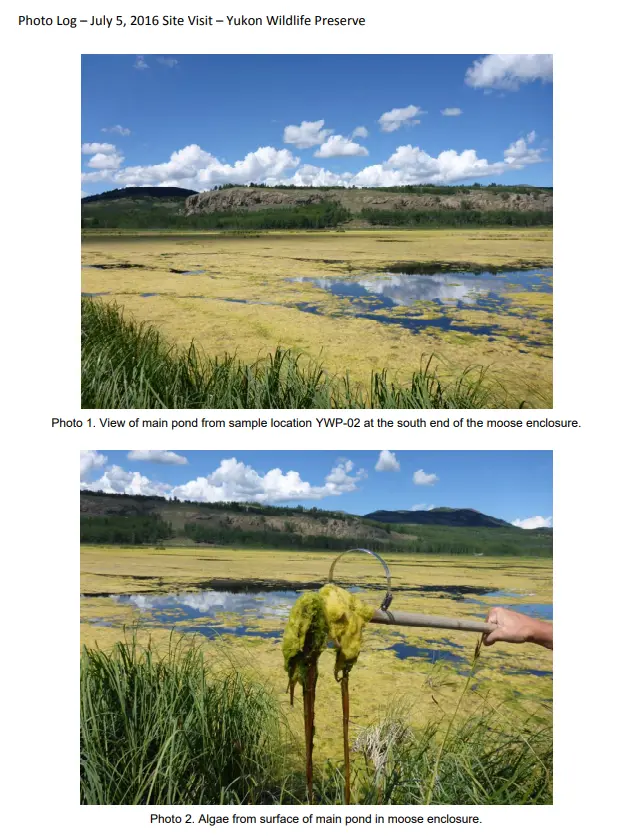

Other creatures like the Musk Ox have evolved communications techniques as adaptations to where they live. In the high arctic where Musk Ox are naturally found, winds blow hard over the tundra and most high frequency sounds are distorted or obliterated by a strong wind. Over many thousands of years Musk Ox evolved to produce a low frequency vocal sound that travels much further and is undistorted by moderate winds. Calves, when communicating with cows or each other, bleat. The pitch of the bleat lowers with maturity. Adults have deeper voices that sound closer to roars and rumbles. Adults also grunt and snort at each other in close proximity. When they are grunting these low frequency sounds it is sometimes possible to feel the vibrations in your chest rather than hear the sounds they are making if you are standing close enough to them.

Human hearing is typically within the audible frequency range of 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. Other species, such as bats and songbirds, produce sounds that are well beyond this limited hearing range of humans. Humans are missing much of the natural symphony in our wilderness because our hearing is not sufficient to hear higher frequencies. Many birds produce sounds that we cannot hear, but our cats and dogs and other wild creatures can.

Birds will often have more than one song which they may use to attract a mate or announce dangers, and while these songs may sound similar, they may have subtle differences that can mean a lot to other birds.

Most bird communications have subtle variations that may seem minor to humans. For example, the common Black-capped Chick-a-dee call is the familiar ‘chick a dee-dee-dee,’ but when alerting danger there is a noticeable increase in the number of dees announced and the increased repetition of the alert call.

Mating songs and danger alerts are different by species and their songs will also change over the seasons, and some birds of the same species may have different songs that have evolved within a geographic community of that particular species. Some other animals will come to know these alert sounds where the birds on guard will make all aware of potential dangers within a specific area. Ground squirrels perform similar audible warning alerts when dangers may be lurking nearby.

Woodpeckers make a wide range of vocal sounds but also rely on the sounds from their hammering on trees and other items to communicate to others. These hammerings also have subtle differences that mean different things that we can only speculate as to their meanings. Did woodpeckers invent their own form of Morse code, and is it different by woodpecker species?

Insects like the ant communicate by leaving scent trails (pheromones) if they are indicating a path to food or some other required resource. They also touch antennae in what is presumed to be a detailed method of communication. Moths and butterflies also depend on pheromone scents primarily for finding mates during their breeding cycle.

Many animals have scent glands of various kinds which they use to mark their territorial boundaries or attract mates. These scent glands may be located on the legs, faces or near their genitals. Some animals must rub objects to deposit their scent while others like the skunk, felines and foxes can also eject their fluid scent some distance. Urine is often used as a scent marker for a variety of species.

Each communication option is limited by physical distance and environmental conditions, as such, the animal tends to communicate with the best option available to them at that time and within the environmental conditions of wind, smoke or precipitation or to avoid announcing their location to predators.

Sight is perhaps the most limited communications sense as it is dependent on available light, although some species have evolved superior eyesight for night viewing, all species are limited to how far they can see clearly, and again there is a spectrum of ability within the animal kingdom which is the result of many millions of generations that adapted to the environment in which they live. The environments the animals live in determines how their eyesight evolved over time. Those that dwell in caves and similar dark places are often close to blindness as they no longer depend on their eyes to navigate in their environment, their other senses have adapted to provide the information about their local environment.

Grassland animals have different sight requirements than animals that live in the forests and jungles. Grazing animals typically have their heads down to eat which has influenced much of their evolutionary development including how long their necks are, the location of their eyes and ears on their skulls, focal distances for both near and far objects and even the visual spectrum they have evolved to see. Caribou have the ability to see in infrared, allowing them to see more features of their vicinity like urine spots left by other animals such as wolves and other predators.

Sound as a communications tool is also limited by distance and influences such as wind or rain which can muffle sounds or distort them such as the rustle of leaves being blown by a strong wind. Some species have hearing that is superior to others, which also is an adaptation based on the environment they must make a living in. Some creatures will lay down and remain still when weather conditions corrupt sound volumes and create distortion, limiting their ability to hear potential dangers near them.

Scent: Messages on the Wind

Scent is perhaps the optimum communications sense animals use to remain aware of the world around them, and while scents may be blown on the wind or distorted or diluted in some way, scent travels further and more clearly than any other communications option.

For an example of sensory limits, let’s examine the Grizzly Bear’s sensory abilities.

- In general terms a bear’s eyesight has an estimated range of about 40 meters depending on light conditions and bears have strong low-light vision abilities and some may have better or lesser sight abilities determined by age and genetics.

- A bear’s hearing is over twice the sensitivity of human hearing and exceeds the human frequency ranges. It is said that bears can detect a human conversation at 300 meters and a camera shutter at 50 meters.

- A bear’s sense of smell has been measured to be capable of detecting food up to 20 kilometers away in most environmental conditions, recognizing scents are also are carried some distances by the wind.

Clearly, scent detection is the optimum communications option available to bears and the majority of other animal species. To this end, they utilize scent marking to make sure others know of their presence.

Lynx, foxes and numerous other species mark their territory with scents they rub or spray onto selected trees or landmarks to define their range boundaries. These marker trees will often include scratch marks made by the animal’s claws which provide a visual clue in addition to the scent.

Scent is also a key indicator of estrus or when a female goes into heat alerting all the males that she is becoming ready to breed.

Male ungulates also employ scent to advertise their locations during their breeding cycles. A bull moose, caribou or elk will urinate on themselves to get their pheromone scent on the breeze and traveling to let both females and males know where they are and their readiness to breed. Predators such as bears and wolves will also detect these pheromones, but for them the message is: potential lunch is over that way.

Honeybees perform an elaborate “waggle dance” in the hive to inform others where new food resources can be found and may also leave a sent marker on the target location to further help hive-mates to locate the new food supply. Other insects utilize scent marking to communicate to their kind.

Sight: The Visual Language of Wildlife

Many bird species rely on their physical appearance for attracting mates. Male birds are usually more colourful and vocal so they attract the attention of any females that may be nearby. Females are not usually coloured as brightly and colourful as the males, partly because they must sit on a nest of eggs when camouflage is helpful for their protection.

As noted above, Body Language is a common method used by animals to share information. For example, when large animals like bison, moose and mountain goats turn sideways to your view, they are saying:

“This is how big I am – Think before you intrude into my space.” They may also paw the ground with a hoof which might mean you missed the first message and now it’s time to move on…quickly.

Whitetail and Mule deer stomp their feet to alert other members of their group that danger may be near and to be on the look-out. Wiggling of ears and rubbing against one another are also methods of body language. A head turned a certain way, lips pulled back and teeth exposed, snorting, head shaking, posturing and even running styles all are communication displays animals employ to communicate with each other.

How animals hold their tails or move them is another signal used to express themselves. The position of the bison’s tail is also a great indication of body language. In addition to switching the tail back and forth to flush insects, frequent tail-switching occurs in a variety of situations, predominantly during play, such as chasing and bounding. You can judge a bison’s mood by watching its tail. When it hangs down and is swishing naturally, the animal is usually calm. But if the tail is sticking straight up, it may be ready to charge. Similarly, if the tail is raised and stiffly held 0° to 90° above the horizontal the animal is displaying some agitation. This is observed most frequently during trotting/running/bounding such as in playful chases, stampedes or in short charges.

Most are familiar with when a dog is wagging its tail to mean it is happy, but it could mean something else entirely for a different species such as a cougar where tail movements can display uncertainty or building excitement or anxiety of the animal.

Body Language: Silent Conversations

Watching the sheep rams you will see many ways they interact with each other. Some of this is easy to understand, like when one is coming to access the feed troughs and usually the younger boys get out of the way when they hear the warning grunts from the dominant elder rams. It is well known rams will get up on their hind legs and smash their horns together like in a mating fight. They may also interlace their horns gently and rub ears with each other or touch the other’s body in some fashion such as one animal rubbing a front leg against the ribs of another standing near. These gestures are common, and we are not always certain what they might mean, but the rams do not appear to be distressed by them, so perhaps it is a form of acknowledgement greeting like a handshake.

Mountain goats appear to employ ESP between themselves, they do grunt and use body language, but there are times when one will walk into an area with a group of other goats that scatter when the other approaches and perhaps wiggles its ears in a particular way or some other gesture that’s difficult for us to perceive. This could also be a demonstration of herd hierarchy through body language or scent where the subordinates know who the boss is and give them lots of space. Some nanny goats display cuts and abrasions on their noses to signify there has been some physical communications in confirming who is dominate and who is subordinate within the herd.

The Role of Environment in Animal Communication

Waterfowl depend on a couple basic methods of communication. The most common is their vocal sounds, quacks and honks are answered back from birds already on the ground, and the incoming birds will also use their remarkable vision to look for others on the ground to confirm it is safe to land. That’s why decoys were invented for hunting as waterfowl are very cautious and are on the lookout for anything they may perceive as a danger waiting for them to land. Waterfowl on the ground employ other methods of communications such as flapping their wings while extending their necks or head bobbing to each other.

It is a myth that duck quacks do not echo. They do, but it may be difficult to hear the echo due to the geography of where ducks are typically found out on a body of water usually away from any echo-producing land formations to reflect the duck’s quack. Larger waterfowl like swans and geese are well known for their loud honks as they migrate overhead, they may also murmur with soft throat sounds as they paddle along the water, usually keeping offspring following in-line behind mom.

Have you ever taken your dog for a walk and notice it sniffs certain places and ignores others? They are searching for scent marks left by other animals. Often, they will urinate on the same spot to let others know they too were in this area. Some say an animal can determine when these scent marks were made, what kind of animal made it and if it is a regular known visitor to the area or if it is a new animal passing through. Similarly, canines are well known to sniff the back end of other canines as a form of introducing themselves and confirming who the other animal is.

Bears, lynx and some other species use a different tactic by selecting a tree, usually on a well used trail, and scratching the bark as high as they can reach. They also leave scent behind and probably some hairs from back-rubbing too. These trees become regular markers for other bears and animals. The scratch marks made by the bears indicate how large they are by their reach and whatever their scent reveals to the rest of the local area.

Arctic Ground Squirrels use their voices to alert others of dangers as they stand watch over their colonies. Watching for predators on the ground and from above; when a threat is sighted the animals begin their chirping and the danger signal is relayed around the area by others to ensure all know about the pending danger. Gophers may also communicate by wagging their tails at each other.

Some animals do not make sounds unless they are in some peril. The Snowshoe Hare depends on stealth and silence to remain healthy and alive, and as such they do not make regular sounds among themselves, but if they have been caught by a predator, they can scream their distress quite loud and clearly.

Most animals have a keen sense of hearing as it is a fundamental sense for their lives. Some species like the deer family have very mobile ears that move to better capture and hear a sound. Many times, a member of the cervid or deer family will give away its hiding location by moving its ears in response to a sound. An uncontrollable reflex, ear movements are similar to a cat’s tail in that the movement is a reflex and cannot be controlled easily.

Hearing is an important sense animals depend on and some creatures have remarkable hearing abilities. A regularly demonstrated example of this at the Preserve is during feeding time for the lynx and foxes. To prevent the animals here at the Preserve from developing a predictable routine, their feeding time is staggered somewhat day by day, but they all know the sound of the food truck and can hear it a substantial distance away. The local ravens, whiskey jacks and magpies know that sound too so when the food truck finally gets up to the carnivore habitats, everybody is in their places waiting for lunch to be served. The animals can distinguish between the food trucks and the tour buses and they know the bus never carries food, so they don’t get too excited when one of them shows up full of visitors.

Enhancing Your Wildlife Experience

While you are visiting the Preserve try to observe how the animals behave with one another and you will witness some of the subtle ways they communicate.

You regular visitors to the Preserve may also notice the changes in the sounds the animals make at different times of the year. Spring sounds are commonly associated with breeding. Arriving migratory birds who do not yet have a mate, will sing their HERE I AM song to appeal to females also seeking a mate. In the springtime it is common to see and hear a robin at the very top of a tree on a still evening singing his heart out to attract a mate or claiming dominance of that particular area.

Once eggs are in the nest the females become silent to better hide their offspring from predators lurking nearby. Momma birds make sounds when dealing with the chicks like announcing the arrival of food or instructions to stay quiet and close to mom. Nesting Great Horned Owls will give a hoot when ravens are flying within eyesight, as ravens have been known to prey on eggs and hatchlings in nests they find, these warning hoots are very clear in their meanings.

For those keen to try their moose calls, our moose may appear to be uninterested because they have heard so many attempts that they don’t pay attention anymore, but like most creatures in the wild, they rely on stealth to survive so they don’t make sounds unless they need to, and moose only need to for a couple weeks each year during the fall rutting season. So, don’t feel bad if the moose don’t acknowledge your call. They probably heard you, but you don’t look or smell like a moose and it is not mating season. But you may hear them as they mumble or complain to one another when together at the feeding stations.

For birding enthusiasts, technology has provided some wonderful new tools to help identify bird species by their songs and visual image. Merlin in a free app developed by Cornell Laboratories. The app converts your cell phone to identify the species of birds by their songs and image.

Communing with nature offers a wide range of stimulation for our human senses and is one of the primary reasons people like to experience the great outdoors. It provides a broad collection of sights, sounds and smells that stimulate our quality of life and tell the story of the environment you may be experiencing at that time.

Imagine how much more we could experience if we humans had the same sensory abilities as the various animals we admire.

Doug Caldwell

Wildlife Interpreter

Doug is one of the Interpretive Wildlife Guides here at the Preserve. An avid angler and hunter he has a broad knowledge of Yukon’s wilderness and the creatures that live here. With a focus on the young visitors to the Preserve, Doug takes the extra time to help our guests to better appreciate the many wonders of the animal kingdom here in the Yukon.