Vernal Species Migration

Vernal Species Migration

Part of Nature’s plan involves animals moving to new locations for two primary reasons:. One is seasonal migration when animals move to a summer location principally to give birth and raise offspring, and the other is permanent migration or colonized range expansion when animals or plants colonize a new range where the critical resources for their continued survival exist in sufficient quantity. Here they will call home and make themselves a part of the local flora and fauna populations.

Migration is a tool used by Nature and benefits many species of animals and the areas where they live. From Monarch Butterflies to Blue Whales, animals migrate back and forth between two primary ranges that support the animal at important stages of every given year. Species temporary absence also provides the area where they live with a break from grazing or predation on a single source of food. Also, physical disturbances and predation is reduced so that grasses and other vegetation can grow back and prey species can rebuild their populations while the predatory species are away on their seasonal migration. Think of it as shift work, there is a split between where creatures work for almost half the year and where they make their home for the other half.

Let’s begin with spring seasonal migration, more properly called the Vernal (Latin for spring) migration when animals move to alternate locations typically in the north with the changing of the seasons only to return later in the year to the area or range they occupied before they migrated. These are often called winter and summer ranges and in many cases involve moving to a place to birth and raise offspring and when these offspring have adequately grown and become a bit more self-sufficient, they return to the other range with mom and dad to spend the rest of their year.

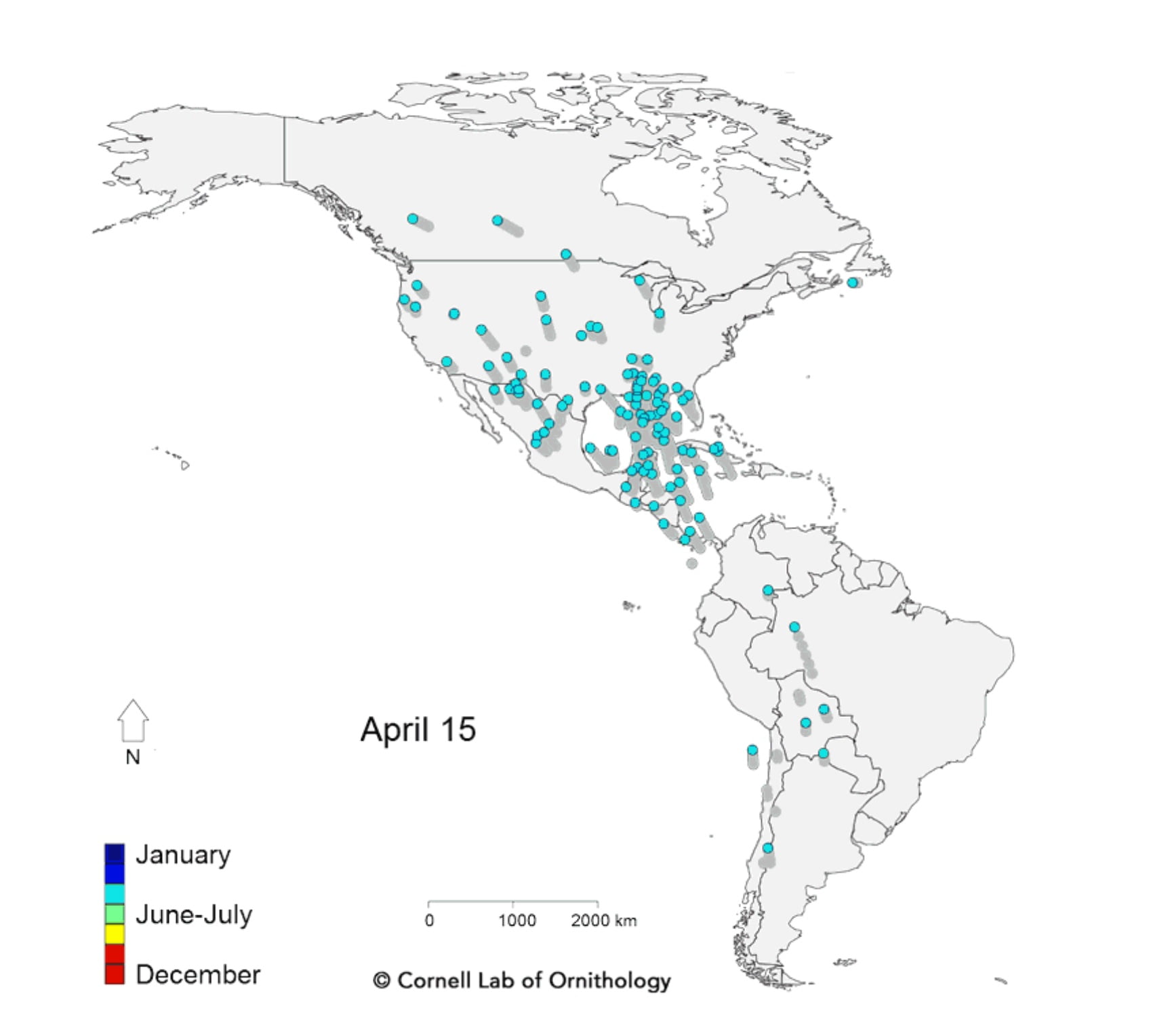

Click here to watch the seasonal movement of birds in North America.

Source Credit: All About Birds

The selection of the spring or winter ranges goes back many hundreds or thousands of generations by species. Some seasonal ranges evolved over time as animals sought out locations that provided the essential basics for them to thrive. Some species migrations have evolved over a tremendous period of time as far back as the Ice Ages, as migration routes are a complex undertaking involving weather conditions and distance to travel while ensuring there is adequate food resources with the right temperatures, humidity and water supply for those species to live comfortably and have the required foods to sustain them on their migration journey. Time is also a very important factor of migration as many other requirements must occur at critical times to ensure the continued health of the animals through all stages of their migrations.

For example, ice in the north must be sufficiently melted to permit arriving waterfowl to eat and remain secure from some predators, similarly, the plants and other vegetation migratory animals depend on should either be grown or growing well enough to sustain the creatures that depend on it when they arrive. These requirements are not just at the destination ranges, but also along the route the animals travel as some migrations may take weeks to complete.

Some species must also learn to endure through varied and sometimes lethal obstacles either created by natural events like landslides, earthquakes and floods, but also by human-made challenges like dams, habitat reduction and new developments and their supportive infrastructure where vital resources needed by the migratory animals have been removed or altered in some way. Ducks and geese must seek out new safe places to stop and reenergize when wetlands they have depended on in previous migrations have been turned into shopping malls and parking lots.

Migratory birds like swans and geese are probably the most visible migratory species as they fly overhead in great flocks honking as they go. Beneath the water’s surface, fish of all kinds like salmon migrate back to their natal streams to lay and fertilize the eggs that will produce their next generation- often within a couple meters of where they were born. Yukon’s rivers connect lakes where our common species of pike, grayling, whitefish and lake trout choose to spend their summers and winters, which may be greatly influenced by the insect hatches and changing water depths resulting from spring melt and freshet flooding. These short seasonal relocations are also considered to be migrations, but are not of the same scope other species like salmon or geese perform.

Photo credit: From Left, Lindsay Caskenette & Jake Paleczny

Barren ground caribou like the Porcupine herd travel vast distances each year enroute to their calving grounds near the north coast. Their migration helps to distribute the impacts of their grazing so that they do not over-consume the vegetation causing harm to the landscape in any given location. Many thousands of caribou can eat a lot and their migration not only ensures more widespread grazing, but also their waste products (poop) are deposited over a greater area, thereby helping to fertilize more of the tundra they depend on each year.

Woodland Caribou at the Preserve.

While all caribou herd migrate the Barren Ground is know for more expansive journeys, particularly the Porcupine Barren Ground Caribou herd.

Photo credit: Jake Paleczny

Insects also migrate usually in search of warmer temperatures and liquid water to lay their eggs and ensure there is an adequate food supply for the young to eat and grow healthy on. A queen honey bee will trigger a brief hive migration when she leaves the hive in search of a new location with better food resources nearby.

Migration is closely tied to a number of annual behavior traits as well. Some bird species may molt (shed their feathers) soon after arriving at their spring destination. Energetically expensive as migration itself molting and replacing feathers after a long journey north is important for the return trip. Also, the cast-off feathers can be used to line their nests against the cool winds of the tundra. However, while molting their ability to fly may be diminished which will put them at greater risk from predators. Just like migration and breeding, molting is ones of the vital parts of a bird’s life.

Video explores molt in the migratory species, the Rusty Blackbird in Southern Yukon.

Source Credit: International Rusty Blackbird Working Group.

Predator birds, raptors like falcons, owls, eagles and various hawks also migrate to these ranges to raise their families and they depend on the ducks, hares, lemmings and other ground-nesting birds as a resource for them and their offspring until it’s time to migrate south again.

Climate change is modifying many of the important conditions some species require to live in a region, the timing of the spring melt is one of the major ones. As warmer spring conditions arrive earlier in the year, some species may need to begin their migration northward sooner to ensure they arrive in time to get a good nesting location, or time their arrival to an important food resource like a caddisfly hatch where millions of little flying insects hatch from a river over a few hours. Both fish and birds gather for these short-lived but important high-protein energy feasts.

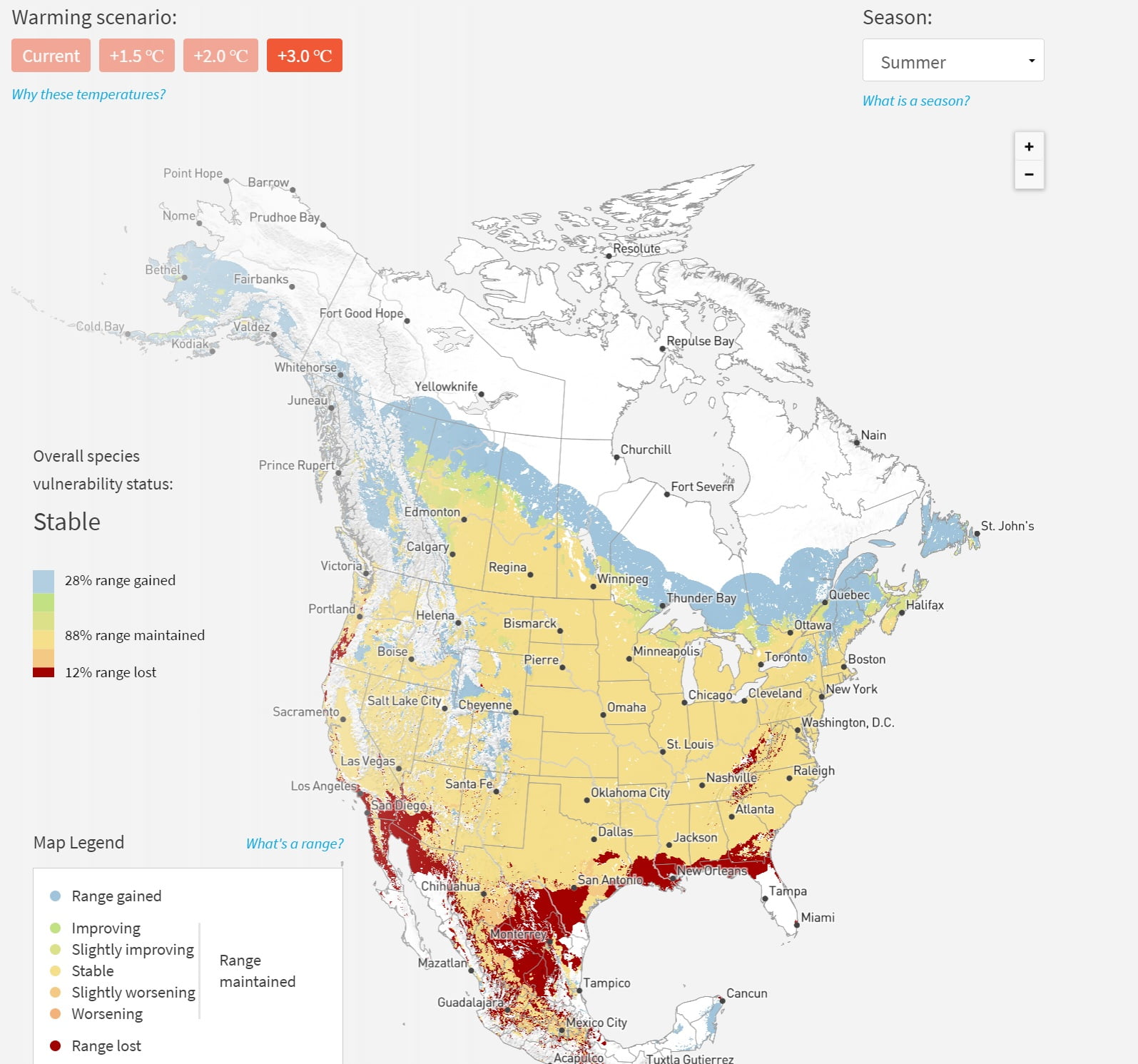

Visit Audonbon.org to learn more about shifting and actaully expanding range for the Barn Swallow in climate change warming scnarios. Source credit: Audubon

Again time is a critical element that can determine success or failure especially when other elements are out of sync. Like a delayed arrival of the warmer spring weather will slow the growth of some vegetation or delay thawing of the ice from waterways which can also create problems if the spring melt happens too early or too dramatically where it may cause rapid snow melt and flood rivers and creeks along migratory routes and nesting locations that create new hazards for the animals. A long lasting winter will also influence how arriving animals settle into their summer homes and make their arrangements for the warmer days to come. Nesting locations and preferred hunting and fishing and grazing spots may be at a premium and first come-first gets is the rule if they are willing to defend their locations.

Migration can be a life or death test for some animals depending on the conditions of the travel route and their intended destinations. Some destinations may be unusable due to new predators making a home there, physical damages caused by floods, fires and the landslides which may cause the animals to seek a new location that meets their needs. They may have to fight to keep their new location as other groups or another species may compete for the same resources they need to survive.

There are many ways human activity interferes with animal migrations in the Detours and Distractions: How Humans Impact Migration Patterns. Explore the educational PDF by National Geographic.

Some predators take advantage of the migratory creatures when they arrive in great numbers. Bears demonstrate this very well as they gather on the streams and rivers to capture migrating salmon returning to spawn. Bears also follow the caribou herds in pursuit of newly born calves trying to keep up with the rest of the herd. Fledgling birds are common prey for Sharp-Shinned Hawks, Shrikes and other small raptors that also may have hungry hatchlings in their nests. Foxes and weasels also prey heavily on eggs and young hatchlings of geese, ducks and other ground-nesting birds.

This photo slide from Yukon photographer, Peter Mather at Ni’iinlii Njik (Fishing Branch) Territorial Park shows the close relationship of predator and prey. Bears will remain active in this region as winter approaches to benefit from the abundance of food in the form of migrating salmon.

Source Credit: Peter Mather Photography

It works the opposite way as well as migratory animals depend on other species to sustain them and in some cases, their choice of destination may depend on resident species and the birthing of their offspring. An example can be found with Peregrine Falcons and other raptors who hunt the lemmings, hares and other rodents born in large numbers on the tundra each spring. Lemmings mature at 5 – 6 weeks of age. They are prolific breeders and may produce 8 litters of up to 6 young each throughout the summer. The gestation period of the female Lemming is 20 days making them one of the primary food resources for carnivorous species, like the Arctic Fox, spending their summer on the tundra.

Arctic Fox at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve.

Photo Credit: J.Paleczny.

Some species like Canada Geese and Tundra Swans mate for life so when they arrive at their springtime destination they can get right to work raising a family, However other species and those just reaching reproductive maturity will need to find a mate, build a nest, breed and raise their new offspring. All of this takes time and each animal is racing the clock and calendar to complete these basic requirements before they have babies which will demand a larger portion of their available time keeping them fed and protected as they grow to adolescence to commence preparations for the migratory trip back to their winter ranges before the winter season arrives, and some years it can come early or later as the present weather trends indicate.

Swan parents and their offspring at the Yukon Wildlife Preserve. In Spring, 2015 a pair built a nest in the moose habitat and had 5 cygnets.

Photo Credit: L.Caskenette

Waterfowl and other creatures that depend on water for their nutrition and safety pay close attention to falling temperatures and the return of ice on the surfaces of ponds and lakes. Other indicators warn of the returning winter conditions, insect populations fall dramatically; leaves change colour and other vegetation stops growing and goes to seed signalling it is time to move south once again.

Some years snow may fall early and in sufficient quantities to make searching for food a greater challenge. Often robins will be seen digging in the snow for insects and berries as they gather together in preparation for their journey south.

Left Photo: American dippers are a delightful winter sight, swimming and singing from icy or rocky perches in fast-flowing waters, such as the Yukon River below the Whitehorse dam.

Right Photo: Winter wannabes like this American robin find small bugs and animals to eat along the muddy shoreline of the Yukon River below the Rotary Centennial Bridge.

Photo Credit and Caption: Jenny Trapnell

Read more from Jenny – A Chance on Winter in What’s Up Yukon.

Migration is an effective tool to ensure the seasonal health of many animal species, but also migration provides habitats some time to regrow while the species are away in their other ranges. Nature’s clock is the movement of the planets and the tilting of the Earth which determine the seasons as winter gives way to spring and new generations are being born. Climate change is also influencing animal species that are well-tuned into these seasonal changes which can be very subtle but are important signs for creatures that need to pay attention to subtle weather changes and the potential impacts on their migration requirements.

Doug Caldwell

Wildlife Interpreter

Doug is one of the Interpretive Wildlife Guides here at the Preserve. An avid angler and hunter he has a broad knowledge of Yukon’s wilderness and the creatures that live here. With a focus on the young visitors to the Preserve, Doug takes the extra time to help our guests to better appreciate the many wonders of the animal kingdom here in the Yukon.